Internationale Militärkampagne, die nach dem 11. September 2001 begann.

Der Krieg gegen den Terror auch bekannt als Global War on Terrorism ist eine internationale Militärkampagne, die von gestartet wurde die Regierung der Vereinigten Staaten nach den Anschlägen vom 11. September gegen die Vereinigten Staaten. [49] Die Benennung der Kampagne bezieht sich auf eine Metapher des Krieges, um auf eine Vielzahl von Aktionen Bezug zu nehmen, die keinen spezifischen Krieg darstellen, wie er traditionell definiert wurde. US-Präsident George W. Bush verwendete den Begriff "Krieg gegen den Terrorismus " am 16. September 2001, [50] [51] und dann "[KrieggegendenTerror" "einige Tage später in einer offiziellen Rede vor dem Kongress. [52] [53] In der letztgenannten Rede erklärte George Bush: "Unser Feind ist ein radikales Netzwerk von Terroristen und jede Regierung, die sie unterstützt." [53] [54] Der Begriff wurde ursprünglich mit einem bestimmten Fokus verwendet über mit al-Qaida assoziierte Länder. Der Begriff wurde sofort von Leuten wie Richard B. Myers, dem Vorsitzenden der Joint Chiefs of Staff, kritisiert. In der Bush-Administration wurden dann differenziertere Begriffe verwendet, um die von den USA geführte internationale Kampagne öffentlich zu definieren. [49] wurde nie als formale Bezeichnung von US-Operationen in der internen Regierungsdokumentation verwendet. [55]

USA Präsident Barack Obama gab am 23. Mai 2013 bekannt, dass der Globale Krieg gegen den Terror vorüber sei. Er sagte, Militär und Geheimdienste würden keinen Krieg gegen eine Taktik führen, sondern sich auf eine bestimmte Gruppe von Netzwerken konzentrieren, die entschlossen seien, die USA zu zerstören. [19460101 Am 28. Dezember 2014 kündigte die Obama-Regierung das Ende der Kampfrolle der US-geführten Mission in Afghanistan an. [57] Der unerwartete Aufstieg der islamischen Staaten im Irak und der Terroristengruppe der Levante (ISIL) - auch bekannt als Islamischer Staat - Irak und Syrien (ISIS) - führte jedoch zu einer neuen Operation gegen den Terror im Nahen Osten und in Südasien, Operation Inhärente Auflösung.

Die Kritik des Krieges gegen den Terror konzentrierte sich auf Moral, Effizienz und Ökonomie. einige, darunter auch der spätere Präsident Barack Obama, [58] [59] [60] [19650101] [61] [61] erhoben Einwände gegen den Ausdruck selbst. Die Vorstellung eines "Krieges" gegen den "Terrorismus" hat sich als umstritten erwiesen. Kritiker behaupteten, dass die Regierungen der Regierungen dazu beigetragen hätten, langjährige politische / militärische Ziele zu verfolgen. [62] verringerte die bürgerlichen Freiheiten, [63] und die Menschenrechte verletzt. Kritiker behaupten auch, dass der Begriff "Krieg" in diesem Zusammenhang nicht angebracht ist (ähnlich wie der Begriff "Krieg gegen Drogen"), da es keinen erkennbaren Feind gibt und es unwahrscheinlich ist, dass der internationale Terrorismus mit militärischen Mitteln beendet werden kann. [64]

Etymology

angibt. Der Ausdruck "Krieg gegen den Terrorismus" wurde speziell verwendet Laufende Militärkampagne der Vereinigten Staaten, des Vereinigten Königreichs und ihrer Verbündeten gegen Organisationen und Regime, die von ihnen als terroristisch eingestuft wurden, und schließt normalerweise andere unabhängige terroristische Eingriffe und Kampagnen wie die von Russland und Indien aus. Auf den Konflikt wurde auch mit anderen Namen als dem War on Terror hingewiesen. Es wurde auch bekannt als:

Geschichte der Verwendung des Satzes und seiner Ablehnung durch die US-Regierung

Dieser Abschnitt muss aktualisiert werden . Aktualisieren Sie diesen Artikel, um aktuelle Ereignisse oder neu verfügbare Informationen widerzuspiegeln. ( April 2018 ) |

Im Jahr 1984 hatte die Reagan-Regierung das CIA-laufende Programm zur Finanzierung der Dschihadisten stark ausgebaut In Afghanistan verwendete der Begriff "Krieg gegen den Terrorismus" den Erlass von Gesetzen zur Bekämpfung terroristischer Gruppierungen nach dem Bombenanschlag von Beirut 1983, bei dem 241 amerikanische und 58 französische Friedenstruppen getötet wurden. [73] US-Vizepräsident Mike Pence nannte die Beirut-Bombardierung von 1983 "die Eröffnungssalve eines Krieges, den wir seitdem geführt haben - den globalen Krieg gegen den Terror." [74]

Das Konzept der USA bei Der Krieg gegen den Terrorismus könnte am 11. September 2001 begonnen haben, als Tom Brokaw, der gerade den Zusammenbruch eines der Türme des World Trade Centers miterlebt hatte, erklärte: "Terroristen haben den Krieg [America]" erklärt. [75] [19659006] Am 16. September 2001 verwendete der US-Präsident George W. Bush in Camp David den Satz "Krieg gegen den Terrorismus" in einem angeblich nicht aufgeschriebenen Kommentar, als er die Frage eines Journalisten nach den Auswirkungen einer verstärkten Strafverfolgungsbehörde auf die USA beantwortete Überwachungsagenturen für die bürgerlichen Freiheiten der Amerikaner: "Dies ist eine neue Art von Bösartigkeit. Und wir verstehen. Und das amerikanische Volk beginnt zu verstehen. Dieser Kreuzzug, dieser Krieg gegen den Terrorismus wird eine Weile dauern. Und das amerikanische Volk muss pat sein ient Ich werde geduldig sein. " [50] [51] Kurz darauf sagte das Weiße Haus, der Präsident bedauere, den Begriff Kreuzzug verwendet zu haben missverstanden worden als Bezug auf die historischen Kreuzzüge: Der Wortkreuzzug wurde nicht erneut verwendet. [76] Am 20. September 2001, während einer Fernsehansprache bei einer gemeinsamen Sitzung des Kongresses, George Bush sagte: "Unser Krieg gegen den Terror beginnt mit Al Kaida, endet aber nicht dort. Es wird nicht enden, bis alle terroristischen Gruppen von globaler Reichweite gefunden, gestoppt und besiegt worden sind. " [52] [53]

Im April 2007 kündigte die britische Regierung öffentlich an, die Nutzung einzustellen [77] Dies wurde kürzlich von Lady Eliza Manningham-Buller erklärt. In ihrer 2011er Reith-Vorlesung, der ehemaligen Leiterin des MI5 sagte, die Anschläge vom 11. September seien "ein Verbrechen, kein Kriegsakt. Ich habe es nie für nützlich gehalten, von einem Krieg gegen den Terror zu sprechen. " [78]

US-Präsident Barack Obama benutzte den Begriff selten, aber in seiner Eröffnungsrede vom 20. Januar 2009 erklärte er:" Unsere Nation ist im Krieg gegen ein weitreichendes Netz von Gewalt und Hass. " [79] Im März 2009 änderte das Verteidigungsministerium offiziell den Namen der Operationen von" Global War on Terror "in" Overseas Contingency Operation "( OCO). [80] Im März 2009 forderte die Obama-Administration die Mitarbeiter des Pentagon auf, die Verwendung des Begriffs zu vermeiden und stattdessen "Overseas Contingency Operation" zu verwenden. [80] Basic Die Ziele der "Krieg gegen den Terror" der Bush-Regierung, wie Al-Qaida-Ziele und der Aufbau internationaler Allianzen zur Terrorismusbekämpfung, bleiben bestehen. [81] [82]

Im Mai 2010 veröffentlichte die Obama-Regierung eine Bericht über seine nationale Sicherheitsstrategie. Das Dokument ist gefallen die Phrase der Bush-Ära "globaler Krieg gegen den Terror" und Verweis auf "islamischer Extremismus", und erklärte: "Dies ist kein globaler Krieg gegen eine Taktik - Terrorismus oder eine Religion - den Islam. Wir befinden uns im Krieg mit einem spezifischen Netzwerk, al-Qaida, und seinen terroristischen Mitgliedern, die die Bemühungen unterstützen, die Vereinigten Staaten, unsere Verbündeten und Partner anzugreifen. " [59]

Im Dezember 2012 Jeh Johnson, der Der General Counsel des US-Verteidigungsministeriums erklärte, der Militärkampf werde durch eine Strafverfolgungsoperation ersetzt, wenn er an der Universität Oxford [83] sprach und voraussagte, dass Al-Qaida so geschwächt sein wird, dass sie unwirksam ist "effektiv zerstört", und somit wird der Konflikt kein bewaffneter Konflikt nach internationalem Recht sein. [84]

Im Mai 2013, zwei Jahre nach der Ermordung von Osama bin Laden, hielt Barack Obama eine angestellte Rede der Begriff globaler Krieg gegen den Terror setzte Anführungszeichen (wie vom Weißen Haus offiziell transkribiert): "Nun machen Sie keinen Fehler, unsere Nation ist immer noch von Terroristen bedroht. ... Aber wir müssen erkennen, dass sich die Bedrohung von derjenigen verändert hat, die am 11. September zu uns gekommen ist. ... Von unserem Einsatz von Drohnen bis zur Inhaftierung terroristischer Verdächtiger werden die Entscheidungen, die wir jetzt treffen, die Art der Nation - und der Welt - bestimmen, die wir unseren Kindern überlassen. Amerika steht also am Scheideweg. Wir müssen die Art und den Umfang dieses Kampfes definieren, sonst wird er uns definieren. Wir müssen an James Madisons Warnung denken, dass "keine Nation ihre Freiheit inmitten einer fortwährenden Kriegsführung bewahren kann". ... In Afghanistan werden wir den Übergang zu afghanischer Verantwortung für die Sicherheit dieses Landes abschließen. ... Über Afghanistan hinaus müssen wir unsere Bemühungen nicht als einen "globalen Krieg gegen den Terror" definieren, sondern als eine Reihe von beharrlichen und gezielten Bemühungen, bestimmte Netzwerke gewalttätiger Extremisten abzubauen, die Amerika bedrohen. In vielen Fällen werden dazu Partnerschaften mit anderen Ländern erforderlich sein. "In der gleichen Rede betonte er jedoch die Rechtmäßigkeit der von den USA unternommenen Militäraktionen und stellte fest, dass der Kongress den Einsatz von Gewalt genehmigt habe, fuhr er fort "Nach innerstaatlichem Recht und internationalem Recht befinden sich die Vereinigten Staaten im Krieg mit Al Kaida, den Taliban und ihren assoziierten Streitkräften. Wir befinden uns im Krieg mit einer Organisation, die im Moment so viele Amerikaner wie möglich töten würde, wenn wir sie nicht zuerst aufhalten würden. Dies ist also ein gerechter Krieg - ein Krieg, der proportional, in letzter Instanz und in Selbstverteidigung geführt wird. " [60] [61]

Der rhetorische Krieg gegen den Terror

Wegen der damit verbundenen Aktionen Der "Krieg gegen den Terrorismus" ist diffus und die Kriterien für die Aufnahme sind unklar. Der politische Theoretiker Richard Jackson hat argumentiert, "der" Krieg gegen den Terrorismus "ist daher gleichzeitig eine Reihe von tatsächlichen Praktiken - Kriege, verdeckte Operationen, Agenturen, und Institutionen - und eine begleitende Reihe von Annahmen, Überzeugungen, Rechtfertigungen und Erzählungen - es ist eine ganze Sprache oder ein Diskurs. " [85] Jackson zitiert unter vielen Beispielen eine Aussage von John Ashcroft, dass" die Angriffe von John Ashcroft " Der 11. September zog eine klare Trennungslinie zwischen Zivilisten und Wildem vor. " [86] Regierungsvertreter bezeichneten" Terroristen "auch als hasserfüllt, verräterisch, barbarisch, verrückt, verdreht, ohne Glauben, parasitär, unmenschlich und am häufigsten ev [87] Amerikaner dagegen wurden als tapfer, liebevoll, großzügig, stark, findig, heroisch und respektvoll der Menschenrechte beschrieben. [88]

Sowohl der Begriff als auch Die Politik, die es bezeichnet, war eine Quelle kontroverser Diskussionen, und Kritiker argumentieren, dass sie dazu benutzt wurde, um einseitigen Präventivkrieg, Menschenrechtsverletzungen und andere Verletzungen des Völkerrechts zu rechtfertigen. [89] [19469036]

Hintergrund

Vorläufer der Anschläge vom 11. September

Die Ursprünge von Al-Qaida lassen sich auf den sowjetisch-afghanischen Krieg (Dezember 1979 - Februar 1989) zurückführen. Die Vereinigten Staaten, das Vereinigte Königreich, Saudi-Arabien, Pakistan und die Volksrepublik China unterstützten die islamistischen afghanischen Mujahadeen-Guerillas gegen die Streitkräfte der Sowjetunion und der Demokratischen Republik Afghanistan. Eine kleine Anzahl von "afghanischen arabischen" Freiwilligen beteiligte sich an dem Kampf gegen die Sowjets, einschließlich Osama bin Laden, aber es gibt keine Hinweise darauf, dass sie Hilfe von außen erhalten haben. Im Mai 1996 begann die von Bin Laden (und später als Al-Qaida neu gegründete) Gruppe Islamische Weltfront für den Jihad gegen Juden und Kreuzritter (WIFJAJC) eine große Operationsbasis in Afghanistan zu bilden, wo das islamistische extremistische Regime von Die Taliban hatten früher im Jahr die Macht ergriffen. [92] Im August 1996 erklärte Bin Laden den Dschihad gegen die Vereinigten Staaten. [93] Im Februar 1998 unterzeichnete Osama bin Laden als Oberhaupt von Al-Qaida eine Fatwa, die den Krieg gegen den Westen und Israel erklärte, [94] [95] später im Mai desselben Jahres. Qaeda veröffentlichte ein Video, in dem der Krieg gegen die USA und den Westen erklärt wurde. [96] [97]

Am 7. August 1998 schlug al-Qaida die US-amerikanischen Botschaften in Kenia und Tansania, darunter 224 Menschen 12 Amerikaner. [98] Als Vergeltungsschlag startete US-Präsident Bill Clinton die Operation Infinite Reach, eine Bombenoffensive im Sudan und in Afghanistan gegen Ziele, von denen die USA behaupteten, sie seien mit WIFJAJC in Verbindung gebracht worden, [99] [100] Die pharmazeutische Fabrik im Sudan wurde als chemische Kriegsführungseinrichtung genutzt. Das Werk produzierte einen Großteil der Malariamittel der Region [101] und rund 50% des pharmazeutischen Bedarfs des Sudan. [102] Die Streiks konnten weder die Anführer des WIFJAJC noch der Taliban töten. [101]

Als nächstes folgten die Angriffspläne des 2. Jahrtausends, zu denen auch ein Bombenanschlag auf den internationalen Flughafen von Los Angeles gehörte. Am 12. Oktober 2000 kam es in der Nähe des Hafens von Jemen zu Bombenanschlägen der USS Cole und 17 US-amerikanische Matrosen wurden getötet. [103]

11. September Angriffe

Am Morgen des Septembers Im Jahr 2001 entführten neunzehn Männer vier Düsenflugzeuge, die alle nach Kalifornien zogen. Nachdem die Entführer die Kontrolle über die Düsenflugzeuge übernommen hatten, teilten sie den Passagieren mit, dass sie eine Bombe an Bord hätten und das Leben der Passagiere und der Besatzung verschonen würden, sobald ihre Forderungen erfüllt waren. Kein Passagier und keine Besatzung hatten den Verdacht, dass sie die Düsenflugzeuge als verwenden würden Selbstmordwaffen, seit es in der Geschichte noch nie geschehen war, und viele vorangegangene Entführungsversuche waren gelöst worden, nachdem die Passagiere und die Besatzung unverletzt geflohen waren, nachdem sie den Flugzeugentführern gehorcht hatten. [104] [105] Die Entführer - Mitglieder der Hamburger Zelle von al-Qaeda [106] - stießen absichtlich zwei Düsenflugzeuge in die Twin Towers des World Trade Centers in New York City. Beide Gebäude brachen innerhalb von zwei Stunden vor den Brandschäden zusammen, die durch die Abstürze verursacht wurden, zerstörten Gebäude in der Nähe und beschädigten andere. Die Entführer stürzten ein drittes Flugzeug in das Pentagon in Arlington County, Virginia, außerhalb von Washington, DC. Das vierte Flugzeug stürzte gegen ein Feld in der Nähe von Shanksville, Pennsylvania, nachdem einige ihrer Passagiere und die Flugbesatzung versucht hatten, die Kontrolle über das Flugzeug wieder zu übernehmen , die die Entführer nach Washington DC weitergeleitet hatten, um auf das Weiße Haus oder das US-Kapitol zu zielen. Keiner der Flüge hatte Überlebende. Bei den Anschlägen kamen 2.977 Opfer und 19 Entführer ums Leben. [107] Fünfzehn der neunzehn waren Bürger Saudi-Arabiens, die anderen stammten aus den Vereinigten Arabischen Emiraten (2), Ägypten und dem Libanon. [108]

Am 13. September rief die NATO zum ersten Mal einen Artikel auf 5 des Nordatlantik-Vertrags [109] Am 18. September 2001 unterzeichnete Präsident Bush die vom Kongress wenige Tage zuvor verabschiedete Genehmigung für den Einsatz militärischer Gewalt gegen Terroristen.

US. Ziele

Die Genehmigung für den Einsatz militärischer Gewalt gegen Terroristen oder "AUMF" wurde am 14. September 2001 gesetzlich festgelegt, um den Einsatz von Streitkräften der Vereinigten Staaten gegen die am 11. September 2001 für die Anschläge Verantwortlichen zu genehmigen alle erforderlichen und angemessenen Gewalttaten gegen jene Nationen, Organisationen oder Personen anwenden, die die Terroranschläge vom 11. September 2001 geplant, genehmigt, begangen oder unterstützt haben, oder solche Organisationen oder Personen beherbergt haben, um künftige internationale Terrorakte zu verhindern die Vereinigten Staaten von solchen Nationen, Organisationen oder Einzelpersonen. Der Kongress erklärt, dass dies eine spezifische gesetzliche Ermächtigung im Sinne von Abschnitt 5 (b) der Resolution der Kriegsmächte von 1973 darstellen soll.

Die Regierung von George W. Bush definierte die folgenden Ziele im Krieg gegen den Terror: [110]

- Besiege Terroristen wie Osama bin Laden, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi und zerstöre ihre Organisationen

- Identify, Terroristen zusammen mit ihren Organisationen aufspüren und abreißen

- Den Terroristen Sponsoring, Unterstützung und Zufluchtsort verweigern

- Das staatliche Sponsoring des Terrorismus beenden

- Errichtung und Aufrechterhaltung eines internationalen Standards für die Rechenschaftspflicht bei der Terrorismusbekämpfung

- Stärkung und Aufrechterhaltung der internationalen Bemühungen zur Terrorismusbekämpfung

- Zusammenarbeit mit willigen und fähigen Staaten

- Widerwillige Staaten überzeugen

- Unwillige Staaten zwingen

- Verbot und Unordnung materielle Unterstützung für Terroristen

- Abschaffung terroristischer Heiligtümer und Häfen

- Verminderung der von Terroristen angestrebten Ausbeutung

- Partnerschaft mit der internationalen Gemeinschaft zur Stärkung schwacher Staaten und zur Verhinderung des (Wieder-) Auftretens des Terrorismus

- Gewinnen Sie den Krieg der Ideale

- Verteidigen Sie US-Bürger und Interessen im In- und Ausland

- Integrieren der nationalen Strategie für die Heimatschutz

- Erlangung der Bekanntheit der Domain

- Verbesserung der Maßnahmen zur Gewährleistung der Integrität, Zuverlässigkeit und Verfügbarkeit kritischer, physischer und informationsbasierter Infrastrukturen im In- und Ausland

- US-Bürger im Ausland schützen

- Sicherstellung einer integrierten Fähigkeit zum Management von Ereignissen

Afghanistan

Operation Enduring Freedom

Operation Enduring Freedom ist die offizielle Bezeichnung der Bush-Regierung für den Krieg in Afghanistan, zusammen mit drei kleineren militärischen Aktionen unter dem Dach des Global War on Terror. Diese globalen Operationen dienen dazu, Al-Qaida-Kämpfer oder angeschlossene Kämpfer zu finden und zu vernichten.

Operation Enduring Freedom - Afghanistan

Am 20. September 2001 stellte George W. Bush der Taliban-Regierung in Afghanistan, dem Islamischen Emirat von Afghanistan, ein Ultimatum, um Osama bin zu übergeben Anführer von Laden und al-Qaida, die im Land operieren oder angegriffen werden. [53] Die Taliban forderten Beweise für Bin Ladens Verbindung zu den Anschlägen vom 11. September, und falls solche Beweise einen Prozess rechtfertigten, boten sie an, einen solchen Prozess vor einem islamischen Gericht durchzuführen. [111] Die USA weigerten sich, Beweise vorzulegen.

Anschließend, im Oktober 2001, marschierten US-Streitkräfte (mit Verbündeten des Vereinigten Königreichs und Koalitionen) in Afghanistan ein, um das Taliban-Regime zu stürzen. Am 7. Oktober 2001 begann die offizielle Invasion mit britischen und amerikanischen Streitkräften, die Luftangriffe auf feindliche Ziele durchführten. Kabul, die Hauptstadt Afghanistans, fiel bis Mitte November. Die restlichen Al-Qaida- und Taliban-Überreste fielen in die zerklüfteten Berge im Osten Afghanistans zurück, hauptsächlich Tora Bora. Im Dezember kämpften die Koalitionstruppen (die USA und ihre Verbündeten) in dieser Region. Man geht davon aus, dass Osama bin Laden während der Schlacht nach Pakistan geflüchtet war. [112] [113]

Im März 2002 starteten die USA und andere NATO- und Nicht-NATO-Truppen die Operation Anaconda mit dem Ziel Zerstörung der verbleibenden Al-Qaida- und Taliban-Truppen im Shah-i-Kot-Tal und Arma-Gebirge in Afghanistan. Die Taliban erlitten schwere Verluste und evakuierten die Region. [114]

Die Taliban gruppierten sich im Westen Pakistans wieder und begannen Ende 2002 eine aufständische Offensive gegen die Koalitionstruppen. [115] Im gesamten Süden und Osten Afghanistans kam es zu Auseinandersetzungen zwischen den aufstrebenden Taliban- und Koalitionsstreitkräften. Die Koalitionstruppen reagierten mit einer Reihe von Militäroffensiven und einer Verstärkung der Truppen in Afghanistan. Im Februar 2010 starteten die Koalitionstruppen zusammen mit anderen militärischen Offensiven die Operation Moshtarak in der Hoffnung, dass sie den Aufstand der Taliban ein für alle Mal zerstören würden. [116] Friedensgespräche sind auch zwischen Taliban-angegliederten Kämpfern und Koalitionstruppen im Gange. [117] Im September 2014 unterzeichneten Afghanistan und die Vereinigten Staaten ein Sicherheitsabkommen, das es den Streitkräften der Vereinigten Staaten und der NATO erlaubt, bis mindestens 2024 in Afghanistan zu bleiben. [118] Die Vereinigten Staaten und andere NATO- und Nicht-NATO-Truppen planen einen Rückzug, [119] mit den Taliban, die behaupten, sie hätten die Vereinigten Staaten und die NATO besiegt, [120] und Obama Die Regierung betrachtet es als Sieg. [121] Im Dezember 2014 begann die ISAF mit ihren Farben und Resolute Support als NATO-Operation in Afghanistan. [122] Die amerikanischen Operationen in den USA werden unter dem Namen "Operation Freedom's Sentinel" fortgesetzt. [123]

International Security Assistance Force

Im Dezember 2001 wurde die von der NATO geführte Internationale Sicherheitsassistententruppe (ISAF) zur Unterstützung der afghanischen Übergangsverwaltung und der ersten Taliban wählte die Regierung. Mit einem erneuten Aufstand der Taliban wurde 2006 bekannt gegeben, dass ISAF die US-Truppen in der Provinz als Teil der Operation Enduring Freedom ersetzen wird.

Die britische 16. Luftangriffsbrigade (später von Royal Marines verstärkt) bildete den Kern der Streitkräfte im Süden Afghanistans, zusammen mit Truppen und Hubschraubern aus Australien, Kanada und den Niederlanden. Die anfängliche Streitmacht bestand aus rund 3.300 Briten, 2.000 Kanadier, 1.400 aus den Niederlanden und 240 aus Australien sowie Spezialeinheiten aus Dänemark und Estland und kleinen Kontingenten aus anderen Nationen. Die monatliche Lieferung von Frachtcontainern über die pakistanische Route zur ISAF in Afghanistan beläuft sich auf über 4.000 [12] in pakistanischen Rupien ] [127] [128]

Irak und Syrien

Der Irak war seit 1990 von den USA als staatlicher Sponsor des Terrorismus gelistet, [129] als Saddam Hussein in Kuwait einmarschierte. Der Irak war auch von 1979 bis 1982 auf der Liste gewesen; Es wurde entfernt, damit die USA den Irak in seinem Krieg mit dem Iran materiell unterstützen konnten. Husseins Regime hatte sich aufgrund des Einsatzes von Chemiewaffen gegen Iraner und Kurden in den achtziger Jahren als ein Problem für die Nachbarn der Vereinten Nationen und des Iraks erwiesen.

Irakische Flugverbotszonen

Im Anschluss an das Waffenstillstandsabkommen, das die Feindseligkeiten im Golfkrieg von 1991 suspendiert (aber nicht offiziell beendet), haben die Vereinigten Staaten und ihre Verbündeten die irakischen Flugverbotszonen zum Schutz der kurdischen Bevölkerung im Irak eingesetzt und die schiitische arabische Bevölkerung, die beide vor und nach dem Golfkrieg vom Hussein-Regime angegriffen wurde, im Norden und Süden des Irak. Die US-Streitkräfte setzten sich bis November 1995 in den Einsatzgebieten der Kampfzone fort und lancierten 1998 die Operation Desert Fox gegen den Irak, nachdem sie die Forderung der USA nach "bedingungsloser Zusammenarbeit" bei Waffeninspektionen nicht erfüllt hatten. [130]

Nach der Operation Desert Fox, im Dezember 1998 kündigte der Irak an, die Flugverbotszonen nicht mehr zu respektieren, und setzte seine Versuche fort, US-Flugzeuge abzuschießen.

Operation Iraqi Freedom

Der Irak-Krieg begann im März 2003 mit einer Luftkampagne, der unmittelbar eine von den USA angeführte Bodeninvasion folgte. Die Bush-Regierung erklärte, die Invasion sei die "ernsthafte Konsequenz", von der in der Resolution 1441 des UN-Sicherheitsrates die Rede war, teilweise durch den Irak, der Massenvernichtungswaffen besaß. Die Bush-Regierung erklärte auch, der Irak-Krieg sei Teil des War on Terror. etwas später hinterfragt oder bestritten.

Der erste Bodenangriff ereignete sich am 21. März 2003 in der Schlacht von Umm Qasr, als britische, amerikanische und polnische Streitkräfte die Kontrolle über die Hafenstadt Umm Qasr übernahmen. [131] Baghdad, Die irakische Hauptstadt fiel im April 2003 an amerikanische Truppen, und Saddam Husseins Regierung löste sich rasch auf. [132] Am 1. Mai 2003 gab Bush bekannt, dass die großen Kampfhandlungen im Irak beendet waren. [133] Es kam jedoch zu einem Aufstand gegen die US-geführte Koalition und die sich neu entwickelnde irakische Militär- und Post-Saddam-Regierung. Die Rebellion, zu der Al-Qaida-Gruppen gehörten, führte zu weit mehr Koalitionsopfern als die Invasion. Andere Elemente des Aufstands wurden von flüchtigen Mitgliedern des Ba'ath-Regimes von Präsident Hussein angeführt, zu dem auch irakische Nationalisten und Panarabisten gehörten. Viele Aufstandsführer sind Islamisten und behaupten, einen Religionskrieg geführt zu haben, um das islamische Kalifat der vergangenen Jahrhunderte wieder herzustellen. [134] Der irakische Präsident Saddam Hussein wurde im Dezember 2003 von den US-Truppen gefangengenommen. Er wurde 2006 hingerichtet.

Im Jahr 2004 wurden die Aufständischen stärker. Die USA führten in Städten wie Nadschaf und Falludscha Angriffe auf Aufständische an.

Im Januar 2007 legte Präsident Bush eine neue Strategie für die Operation Iraqi Freedom vor, die auf Theorien und Taktiken des Aufstands gegen Aufstände von General David Petraeus basiert. Der Truppenanstieg im Irak-Krieg von 2007 war Teil dieses "neuen Weges". Zusammen mit der Unterstützung der USA, die die sunnitischen Gruppen, die er zuvor besiegt hatte, unterstützt hatte, wurde der weithin anerkannte dramatische Rückgang der Gewalt um bis zu 80% zugeschrieben.

Operation New Dawn

Der Krieg trat am 1. September 2010 in eine neue Phase ein, [135] mit dem offiziellen Ende der US-amerikanischen Kampfhandlungen. Die letzten US-Truppen verließen den Irak am 18. Dezember 2011. [136]

Operation Inherent Resolve (Syrien und Irak)

In einer großen Spaltung in den Reihen der Al-Qaida-Organisation war die irakische Franchise, bekannt als Al Qaida im Irak marschierte heimlich in Syrien und die Levante ein und begann, am anhaltenden Bürgerkrieg in Syrien teilzunehmen. Sie erlangte genug Unterstützung und Kraft, um die westlichen Provinzen des Irak unter dem Namen des Islamischen Staates Irak und der Levante (ISIS / ISIL) wieder einzunehmen in einem blitzkriegsähnlichen Vorgehen über einen großen Teil des Landes und die Kombination des irakischen Aufstands und des syrischen Bürgerkriegs in einem einzigen Konflikt. [137] Aufgrund ihrer extremen Brutalität und einer vollständigen Änderung ihrer gesamten Ideologie verurteilte Al Qaidas Organisation in Zentralasien schließlich den IS und wies ihre Mitgliedsorganisationen an, alle Verbindungen zu dieser Organisation abzuschneiden. [138] Viele Analysten [ who? glauben, dass Al Qaida und ISIL aufgrund dieses Schismas nun in einem Wettbewerb stehen, um den Titel der weltweit mächtigsten Terroristenorganisation zu erhalten. [139]

Die Obama-Regierung begann sich mit einer Serie von Luftangriffen, die auf ISIS ab 10. August 2014 gerichtet waren, wieder im Irak zu engagieren. [140] Am 9. September 2014 erklärte Präsident Obama, er habe die Autorität, die er ergreift, um die militante Gruppe, die als Islamischer Staat im Irak und in der Levante bekannt ist, zu vernichten, wobei er die 2001 erteilte Genehmigung für den Einsatz militärischer Gewalt gegen Terroristen geltend machte keine zusätzliche Genehmigung des Kongresses erfordern. [141] Am darauffolgenden Tag am 10. September 2014 hielt Präsident Barack Obama eine Fernsehansprache über ISIL, in der er erklärte: "Unser Ziel ist klar: Wir werden ISIL durch eine umfassende und nachhaltige Strategie zur Terrorismusbekämpfung degradieren und letztendlich zerstören." [142] Obama hat die Entsendung weiterer US-Streitkräfte in den Irak sowie die Genehmigung direkter militärischer Operationen gegen ISIL in Syrien genehmigt. [142] In der Nacht vom 21. auf den 22. September starteten die Vereinigten Staaten, Saudi-Arabien, Bahrain, die Vereinigten Arabischen Emirate, Jordanien und Katar Luftangriffe auf den IS in Syrien. [ Zitierbedarf ]

Im Oktober 2014 wurde berichtet, dass das US-Verteidigungsministerium Militäreinsätze gegen ISIL hinsichtlich der Wahlkampfmedaillenvergabe unter Operation Enduring Freedom hält. [143] Am 15. Oktober wurde die militärische Intervention als "Operation Inherent Resolve" bekannt. 19459168 [144]

Pakistan

Nach den Anschlägen vom 11. September 2001 trat der ehemalige pakistanische Präsident Pervez Musharraf gegen die Taliban-Regierung ein in Afghanistan nach einem Ultimatum des damaligen US-Präsidenten George W. Bush. Musharraf stimmte zu, den USA die Verwendung von drei Luftstützpunkten für die Operation Enduring Freedom zu gewähren. US-Außenminister Colin Powell und andere US-Regierungsbeamte trafen sich mit Musharraf. Am 19. September 2001 sprach Musharraf vor dem pakistanischen Volk und erklärte, Pakistan habe zwar gegen militärische Taktiken gegen die Taliban Einspruch erhoben, könnte jedoch durch ein Bündnis von Indien und den USA gefährdet werden, wenn es nicht kooperiere. Im Jahr 2006 bezeugte Musharraf, dass diese Haltung durch Drohungen aus den USA unter Druck gesetzt wurde, und enthüllte in seinen Memoiren, dass er die Vereinigten Staaten als Kriegsgegner "als Kriegsgegner" bezeichnet hatte und entschied, dass dies für Pakistan ein Verlust bedeuten würde. [145]

Am 12. Januar 2002 hielt Musharraf eine Rede gegen den islamischen Extremismus. Er verurteilte unmissverständlich alle Terrorakte und versprach, den islamischen Extremismus und die Gesetzlosigkeit in Pakistan selbst zu bekämpfen. Er erklärte, seine Regierung sei entschlossen, Extremismus auszurotten, und machte deutlich, dass die verbotenen militanten Organisationen unter keinem neuen Namen wieder auftauchen dürfen. Er sagte: "Die kürzliche Entscheidung, extremistische Gruppen zu verbieten, die die Militanz fördern, wurde nach eingehenden Konsultationen im nationalen Interesse getroffen. Sie wurde nicht unter ausländischem Einfluss genommen." [146]

Im Jahr 2002 führte die von Musharraf geführte Regierung Gegen die dschihadistischen Organisationen und Gruppen, die den Extremismus befürworteten, verhafteten sie sich und verhafteten Maulana Masood Azhar, den Vorsitzenden der Jaish-e-Mohammed, und Hafiz Muhammad Saeed, den Chef der Lashkar-e-Taiba, und nahmen Dutzende von Aktivisten in Gewahrsam. Am 12. Januar wurde den Gruppen ein offizielles Verbot auferlegt. [147] Later that year, the Saudi born Zayn al-Abidn Muhammed Hasayn Abu Zubaydah was arrested by Pakistani officials during a series of joint U.S.-Pakistan raids. Zubaydah is said to have been a high-ranking al-Qaeda official with the title of operations chief and in charge of running al-Qaeda training camps.[148] Other prominent al-Qaeda members were arrested in the following two years, namely Ramzi bin al-Shibh, who is known to have been a financial backer of al-Qaeda operations, and Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who at the time of his capture was the third highest-ranking official in al-Qaeda and had been directly in charge of the planning for the 11 September attacks.

In 2004, the Pakistan Army launched a campaign in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan's Waziristan region, sending in 80,000 troops. The goal of the conflict was to remove the al-Qaeda and Taliban forces in the area.

After the fall of the Taliban regime, many members of the Taliban resistance fled to the Northern border region of Afghanistan and Pakistan where the Pakistani army had previously little control. With the logistics and air support of the United States, the Pakistani Army captured or killed numerous al-Qaeda operatives such as Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, wanted for his involvement in the USS Cole bombing, the Bojinka plot, and the killing of Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl.

The United States has carried out a campaign of Drone attacks on targets all over the Federally Administered Tribal Areas. However, the Pakistani Taliban still operates there. To this day it is estimated that 15 U.S. soldiers were killed while fighting al-Qaeda and Taliban remnants in Pakistan since the War on Terror began.[149]

Osama bin Laden, who was of many founders of al-Qaeda, his wife, and son, were all killed on 2 May 2011, during a raid conducted by the United States special operations forces in Abbottabad, Pakistan.[150]

The use of drones by the Central Intelligence Agency in Pakistan to carry out operations associated with the Global War on Terror sparks debate over sovereignty and the laws of war. The U.S. Government uses the CIA rather than the U.S. Air Force for strikes in Pakistan to avoid breaching sovereignty through military invasion. The United States was criticized by[according to whom?] a report on drone warfare and aerial sovereignty for abusing the term 'Global War on Terror' to carry out military operations through government agencies without formally declaring war.

In the three years before the attacks of 11 September, Pakistan received approximately US$9 million in American military aid. In the three years after, the number increased to US$4.2 billionmaking it the country with the maximum funding post 9/11.

Baluchistan

An uprising in Baluchistan began after Pakistan invaded and occupied the territory in 1948. Various NGOs have reported human rights violations in committed by Pakistani armed forces. Approximately 18,000 Baluch residents are reportedly missing and about 2000 have been killed.[151]

Brahamdagh Bugti, leader of the Baloch Republican Party, stated in a 2008 interview that he would accept aid from India, Afghanistan, and Iran in defending Baluchistan against Pakistani aggression.[152] Pakistan has repeatedly accused India of supporting Baloch rebels,[153][154] and David Wright-Neville writes that outside Pakistan, some Western observers also believe that India secretly funds the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA).[155]

Trans-Sahara (Northern Africa)

Operation Enduring Freedom – Trans Sahara

Operation Enduring Freedom – Trans Sahara (OEF-TS) is the name of the military operation conducted by the U.S. and partner nations in the Sahara/Sahel region of Africa, consisting of counter-terrorism efforts and policing of arms and drug trafficking across central Africa.

The conflict in northern Mali began in January 2012 with radical Islamists (affiliated to al-Qaeda) advancing into northern Mali. The Malian government had a hard time maintaining full control over their country. The fledgling government requested support from the international community on combating the Islamic militants. In January 2013, France intervened on behalf of the Malian government's request and deployed troops into the region. They launched Operation Serval on 11 January 2013, with the hopes of dislodging the al-Qaeda affiliated groups from northern Mali.[156]

Horn of Africa and the Red Sea

Operation Enduring Freedom – Horn of Africa

This extension of Operation Enduring Freedom was titled OEF-HOA. Unlike other operations contained in Operation Enduring Freedom, OEF-HOA does not have a specific organization as a target. OEF-HOA instead focuses its efforts to disrupt and detect militant activities in the region and to work with willing governments to prevent the reemergence of militant cells and activities.[157]

In October 2002, the Combined Joint Task Force - Horn of Africa (CJTF-HOA) was established in Djibouti at Camp Lemonnier.[158] It contains approximately 2,000 personnel including U.S. military and special operations forces (SOF) and coalition force members, Combined Task Force 150 (CTF-150).

Task Force 150 consists of ships from a shifting group of nations, including Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Pakistan, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. The primary goal of the coalition forces is to monitor, inspect, board and stop suspected shipments from entering the Horn of Africa region and affecting the United States' Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Included in the operation is the training of selected armed forces units of the countries of Djibouti, Kenya and Ethiopia in counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency tactics. Humanitarian efforts conducted by CJTF-HOA include rebuilding of schools and medical clinics and providing medical services to those countries whose forces are being trained.

The program expands as part of the Trans-Saharan Counterterrorism Initiative as CJTF personnel also assist in training the armed forces of Chad, Niger, Mauritania and Mali. However, the War on Terror does not include Sudan, where over 400,000 have died in an ongoing civil war.

On 1 July 2006, a Web-posted message purportedly written by Osama bin Laden urged Somalis to build an Islamic state in the country and warned western governments that the al-Qaeda network would fight against them if they intervened there.[159]

Somalia has been considered a "failed state" because its official central government was weak, dominated by warlords and unable to exert effective control over the country. Beginning in mid-2006, the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), an Islamist faction campaigning on a restoration of "law and order" through Sharia law, had rapidly taken control of much of southern Somalia.

On 14 December 2006, the U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Jendayi Frazer claimed al-Qaeda cell operatives were controlling the Islamic Courts Union, a claim denied by the ICU.[160]

By late 2006, the UN-backed Transitional Federal Government (TFG) of Somalia had seen its power effectively limited to Baidoa, while the Islamic Courts Union controlled the majority of southern Somalia, including the capital of Mogadishu. On 20 December 2006, the Islamic Courts Union launched an offensive on the government stronghold of Baidoa and saw early gains before Ethiopia intervened for the government.

By 26 December, the Islamic Courts Union retreated towards Mogadishu, before again retreating as TFG/Ethiopian troops neared, leaving them to take Mogadishu with no resistance. The ICU then fled to Kismayo, where they fought Ethiopian/TFG forces in the Battle of Jilib.

The Prime Minister of Somalia claimed that three "terror suspects" from the 1998 United States embassy bombings are being sheltered in Kismayo.[161] On 30 December 2006, al-Qaeda deputy leader Ayman al-Zawahiri called upon Muslims worldwide to fight against Ethiopia and the TFG in Somalia.[162]

On 8 January 2007, the U.S. launched the Battle of Ras Kamboni by bombing Ras Kamboni using AC-130 gunships.[163]

On 14 September 2009, U.S. Special Forces killed two men and wounded and captured two others near the Somali village of Baarawe. Witnesses claim that helicopters used for the operation launched from French-flagged warships, but that could not be confirmed. A Somali-based al-Qaida affiliated group, the Al-Shabaab, has verified the death of "sheik commander" Saleh Ali Saleh Nabhan along with an unspecified number of militants.[164] Nabhan, a Kenyan, was wanted in connection with the 2002 Mombasa attacks.[165]

Philippines

Operation Enduring Freedom – Philippines

In January 2002, the United States Special Operations Command, Pacific deployed to the Philippines to advise and assist the Armed Forces of the Philippines in combating Filipino Islamist groups.[166] The operations were mainly focused on removing the Abu Sayyaf group and Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) from their stronghold on the island of Basilan.[167] The second portion of the operation was conducted as a humanitarian program called "Operation Smiles". The goal of the program was to provide medical care and services to the region of Basilan as part of a "Hearts and Minds" program.[168][169] Joint Special Operations Task Force – Philippines disbanded in June 2014,[170] ending a successful 12-year mission.[171] After JSOTF-P had disbanded, as late as November 2014, American forces continued to operate in the Philippines under the name "PACOM Augmentation Team", until February 24, 2015.[172][173] By 2018, American operations within the Philippines against terrorist was renamed Operation Pacific Eagle, which involves as many as 300 advisers.[174]

Yemen

The United States has also conducted a series of military strikes on al-Qaeda militants in Yemen since the War on Terror began.[175] Yemen has a weak central government and a powerful tribal system that leaves large lawless areas open for militant training and operations. Al-Qaeda has a strong presence in the country.[176] On 31 March 2011, AQAP declared the Al-Qaeda Emirate in Yemen after its captured most of Abyan Governorate.[177]

The U.S., in an effort to support Yemeni counter-terrorism efforts, has increased their military aid package to Yemen from less than $11 million in 2006 to more than $70 million in 2009, as well as providing up to $121 million for development over the next three years.[178]

U.S. allies in the Middle East

Israel

Israel has been fighting terrorist groups such Hezbollah, Hamas, and Islamic Jihad, who are all Iran's proxies aimed at Iran's objective to destroy Israel. According to the Clarion Project: "Since 1979, Iran has been responsible for countless terrorist plots, directly through regime agents or indirectly through proxies like Hamas and Hezbollah.[179] In 2006, U.S. President [George W Bush] said that Israel's war on terrorist group Hezbollah was part of war on terror.[180]

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia witnessed multiple terror attacks from different groups such as Al-Qaeda, whose leader, Osama Bin Laden, declared war on the Saudi government. On June 16, 1996, the Khobar Towers bombing killed 19 U.S. soldiers. The 9/11 Commission concluded that Hezbollah, likely with the support of the Iranian regime, was the perpetrator of that bombing in Saudi Arabia. It said there are "signs" that Al-Qaeda also played a role.[179]

Libya

On 19 March 2011, a multi-state coalition began a military action in Libya, ostensibly to implement United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973. The United Nations Intent and Voting was to have "an immediate ceasefire in Libya, including an end to the current attacks against civilians, which it said might constitute crimes against humanity" ... "imposing a ban on all flights in the country's airspace – a no-fly zone – and tightened sanctions on the Qadhafi regime and its supporters." The resolution was taken in response to events during the Libyan Civil War,[181] and military operations began, with American and British naval forces firing over 110 Tomahawk cruise missiles,[182] the French Air Force, British Royal Air Force, and Royal Canadian Air Force[183] undertaking sorties across Libya and a naval blockade by Coalition forces.[184] French jets launched air strikes against Libyan Army tanks and vehicles.[185][186] The Libyan government response to the campaign was totally ineffectual, with Gaddafi's forces not managing to shoot down a single NATO plane despite the country possessing 30 heavy SAM batteries, 17 medium SAM batteries, 55 light SAM batteries (a total of 400–450 launchers, including 130–150 SA-6 launchers and some SA-8 launchers), and 440–600 short-range air-defense guns.[187][188] The official names for the interventions by the coalition members are Opération Harmattan by France; Operation Ellamy by the United Kingdom; Operation Mobile for the Canadian participation and Operation Odyssey Dawn for the United States.[189]

From the beginning of the intervention, the initial coalition of Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Italy, Norway, Qatar, Spain, UK, and U.S.[190][191][192][193][194] expanded to nineteen states, with newer states mostly enforcing the no-fly zone and naval blockade or providing military logistical assistance. The effort was initially largely led by France and the United Kingdom, with command shared with the United States. NATO took control of the arms embargo on 23 March, named Operation Unified Protector. An attempt to unify the military leadership of the air campaign (while keeping political and strategic control with a small group), first failed over objections by the French, German, and Turkish governments.[195][196] On 24 March, NATO agreed to take control of the no-fly zone, while command of targeting ground units remains with coalition forces.[197][198][199] The handover occurred on 31 March 2011 at 06:00 UTC (08:00 local time). NATO flew 26,500 sorties since it took charge of the Libya mission on 31 March 2011.

Fighting in Libya ended in late October following the death of Muammar Gaddafi, and NATO stated it would end operations over Libya on 31 October 2011. Libya's new government requested its mission to be extended to the end of the year,[200] but on 27 October, the Security Council voted to end NATO's mandate for military action on 31 October.[201]

NBC News reported that in mid-2014, ISIS had about 1,000 fighters in Libya. Taking advantage of a power vacuum in the center of the country, far from the major cities of Tripoli and Benghazi, ISIS expanded rapidly over the next 18 months. Local militants were joined by jihadists from the rest of North Africa, the Middle East, Europe and the Caucasus. The force absorbed or defeated other Islamist groups inside Libya and the central ISIS leadership in Raqqa, Syria, began urging foreign recruits to head for Libya instead of Syria. ISIS seized control of the coastal city of Sirte in early 2015 and then began to expand to the east and south. By the beginning of 2016, it had effective control of 120 to 150 miles of coastline and portions of the interior and had reached Eastern Libya's major population center, Benghazi. In spring 2016, AFRICOM estimated that ISIS had about 5,000 fighters in its stronghold of Sirte.[202]

However, the indigenous rebel groups who had staked their claims to Libya and turned their weapons on ISIS—with the help of airstrikes by Western forces, including U.S. drones, the Libyan population resented the outsiders who wanted to establish a fundamentalist regime on their soil. Militias loyal to the new Libyan unity government, plus a separate and rival force loyal to a former officer in the Qaddafi regime, launched an assault on ISIS outposts in Sirte and the surrounding areas that lasted for months. According to U.S. military estimates, ISIS ranks shrank to somewhere between a few hundred and 2,000 fighters. In August 2016, the U.S. military began airstrikes that, along with continued pressure on the ground from the Libyan militias, pushed the remaining ISIS fighters back into Sirte, In all, U.S. drones and planes hit ISIS nearly 590 times, the Libyan militias reclaimed the city in mid-December.[202] On January 18, 2017, ABC News reported that two USAF B-2 bombers struck two ISIS camps 28 miles (45 km) south of Sirte, the airstrikes targeted between 80 and 100 ISIS fighters in multiple camps, an unmanned aircraft also participated in the airstrikes. NBC News reported that as many as 90 ISIS fighters were killed in the strike, a U.S. defense official said that "This was the largest remaining ISIS presence in Libya," and that "They have been largely marginalized, but I am hesitant to say they have been eliminated in Libya."[202]

Other military operations

Operation Active Endeavour

Operation Active Endeavour is a naval operation of NATO started in October 2001 in response to the 11 September attacks. It operates in the Mediterranean and is designed to prevent the movement of militants or weapons of mass destruction and to enhance the security of shipping in general.[203]

Fighting in Kashmir

In a 'Letter to American People' written by Osama bin Laden in 2002, he stated that one of the reasons he was fighting America is because of its support of India on the Kashmir issue.[204][205] While on a trip to Delhi in 2002, U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld suggested that Al-Qaeda was active in Kashmir, though he did not have any hard evidence.[206][207] In 2002, The Christian Science Monitor published an article claiming that Al-Qaeda and its affiliates were "thriving" in Pakistan-administered Kashmir with the tacit approval of Pakistan's National Intelligence agency Inter-Services Intelligence.[208] A team of Special Air Service and Delta Force was sent into Indian-administered Kashmir in 2002 to hunt for Osama bin Laden after reports that he was being sheltered by the Kashmiri militant group Harkat-ul-Mujahideen.[209] U.S. officials believed that Al-Qaeda was helping organize a campaign of terror in Kashmir to provoke conflict between India and Pakistan. Fazlur Rehman Khalil, the leader of the Harkat-ul-Mujahideen, signed al-Qaeda's 1998 declaration of holy war, which called on Muslims to attack all Americans and their allies.[210] Indian sources claimed that In 2006, Al-Qaeda claimed they had established a wing in Kashmir; this worried the Indian government.[211] India also argued that Al-Qaeda has strong ties with the Kashmir militant groups Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed in Pakistan.[212] While on a visit to Pakistan in January 2010, U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Gates stated that Al-Qaeda was seeking to destabilize the region and planning to provoke a nuclear war between India and Pakistan.[213]

In September 2009, a U.S. Drone strike reportedly killed Ilyas Kashmiri, who was the chief of Harkat-ul-Jihad al-Islami, a Kashmiri militant group associated with Al-Qaeda.[214][215] Kashmiri was described by Bruce Riedel as a 'prominent' Al-Qaeda member,[216] while others described him as the head of military operations for Al-Qaeda.[217]Waziristan had now become the new battlefield for Kashmiri militants, who were now fighting NATO in support of Al-Qaeda.[218]

On 8 July 2012, Al-Badar Mujahideen, a breakaway faction of Kashmir centric terror group Hizbul Mujahideen, on the conclusion of their two-day Shuhada Conference called for a mobilization of resources for continuation of jihad in Kashmir.[219]

American military intervention in Cameroon

In October 2015, the U.S. began deploying 300 soldiers[220] to Cameroon, with the invitation of the Cameroonian government, to support African forces in a non-combat role in their fight against ISIS insurgency in that country. The troops' primary missions will revolve around providing intelligence support to local forces as well as conducting reconnaissance flights.[221]

International military support

The invasion of Afghanistan is seen to have been the first action of this war, and initially involved forces from the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Afghan Northern Alliance. Since the initial invasion period, these forces were augmented by troops and aircraft from Australia, Canada, Denmark, France, Italy, Netherlands, New Zealand and Norway amongst others. In 2006, there were about 33,000 troops in Afghanistan.

On 12 September 2001, less than 24 hours after the 11 September attacks in New York City and Washington, D.C., NATO invoked Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty and declared the attacks to be an attack against all 19 NATO member countries. Australian Prime Minister John Howard also stated that Australia would invoke the ANZUS Treaty along similar lines.[222]

In the following months, NATO took a broad range of measures to respond to the threat of terrorism. On 22 November 2002, the member states of the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC) decided on a Partnership Action Plan against Terrorism, which explicitly states, "[The] EAPC States are committed to the protection and promotion of fundamental freedoms and human rights, as well as the rule of law, in combating terrorism."[223] NATO started naval operations in the Mediterranean Sea designed to prevent the movement of terrorists or weapons of mass destruction as well as to enhance the security of shipping in general called Operation Active Endeavour.

Support for the U.S. cooled when America made clear its determination to invade Iraq in late 2002. Even so, many of the "coalition of the willing" countries that unconditionally supported the U.S.-led military action have sent troops to Afghanistan, particular neighboring Pakistan, which has disowned its earlier support for the Taliban and contributed tens of thousands of soldiers to the conflict. Pakistan was also engaged in the War in North-West Pakistan (Waziristan War). Supported by U.S. intelligence, Pakistan was attempting to remove the Taliban insurgency and al-Qaeda element from the northern tribal areas.[224]

Terrorist attacks and failed plots since 9/11

Al-Qaeda

Since 9/11, Al-Qaeda and other affiliated radical Islamist groups have executed attacks in several parts of the world where conflicts are not taking place. Whereas countries like Pakistan have suffered hundreds of attacks killing tens of thousands and displacing much more.

- The 2002 Bali bombings in Indonesia were committed by various members of Jemaah Islamiyah, an organization linked to Al-Qaeda.

- The 2003 Casablanca bombings were carried out by Salafia Jihadia, an Al-Qaeda affiliate.

- After the 2003 Istanbul bombings, Turkey charged 74 people with involvement, including Syrian Al-Qaeda member Loai al-Saqa.

- The 2004 Madrid train bombings in Spain were "inspired by" Al-Qaeda, though no direct involvement has been established.

- The 7 July 2005 London bombings in the United Kingdom were perpetrated by four homegrown terrorists, one of whom appeared in an edited video with a known Al-Qaeda operative, though the British government denies Al-Qaeda involvement.

- Al Qaeda claimed responsibility for the 11 April 2007 Algiers bombings in Algeria.

- The 2007 Glasgow International Airport attack in the United Kingdom was carried out by a pair of bombers whose laptops and suicide notes included videos and speeches referencing Al-Qaeda, though no direct involvement was established.

- The 2009 Fort Hood shooting in the United States was committed by Nidal Malik Hasan, who had been in communication with Anwar al-Awlaki, though the Department of Defense classifies the shooting as an incidence of workplace violence.

- Morocco blames Al-Qaeda for the 2011 Marrakech bombing, though Al-Qaeda denies involvement.

- The 2012 Toulouse and Montauban shootings in France were committed by Mohammed Merah, who reportedly had familial ties to Al-Qaeda, along with a history of petty crime and psychological issues. Merah claimed ties to Al-Qaeda, though French authorities deny any connection.

- To date, no one has been convicted for the 2012 U.S. Consulate attack in Benghazi in Libya, and no one has claimed responsibility. Branches of Al-Qaeda, Al-Qaeda affiliates, and individuals "sympathetic to Al-Qaeda" are blamed.

- The gunmen in the 2015 Charlie Hebdo shooting in Paris identified themselves as belonging to Al-Qaeda's branch in Yemen.

There may also have been several additional planned attacks that were not successful.

The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL)

- 2013 Reyhanlı bombings in Turkey that led to 52 deaths and the injury of 140 people.

- 2014 Canadian parliament shootings, an ISIL-inspired attack on Canada's Parliament, resulting in the death of a Canadian soldier, as well as that of the perpetrator.

- 2015 Porte de Vincennes siege perpetrated by Amedy Coulibaly in Paris, which led to four deaths and the injury of nine others.

- 2015 Corinthia Hotel attack on 27 January in Libya that resulted in 10 deaths.

- 2015 Sana'a mosque bombings on 20 March that led to the death of 142 and injury of 351 people.

- 2015 Curtis Culwell Center attack on 3 May 2015 that resulted in the injury of one security officer.

- November 2015 Paris attacks on the 13th that left at least 137 dead and injured at least 352 civilians caused France to be put under a state of emergency, close its borders and deploy three French contingency plans.[225] Islamic State claimed responsibility for the attacks,[226] with French President François Hollande later stated the attacks were carried out "by the Islamic state with internal help".[227]

- 2015 San Bernardino attack on 2 December 2015, two gunmen attacked a county building in San Bernardino, California killing 16 people and injuring 24 others.[228]

- 2016 Brussels bombing on 22 March 2016 two bombing attacks, first at Brussels Airport and the second at the Maalbeek/Maelbeek metro station, killed 35 people and injured more than 300.

- 2016 Orlando nightclub shooting on 12 June 2016 a gunman opened fire at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida killing 50 people and wounding 53 others. It was the second worst mass shooting in U.S. history.[229]

- As well as a thwarted 2014 mass-beheading plot in Australia.

Post 9/11 events inside the United States

In addition to military efforts abroad, in the aftermath of 9/11, the Bush Administration increased domestic efforts to prevent future attacks. Various government bureaucracies that handled security and military functions were reorganized. A new cabinet-level agency called the United States Department of Homeland Security was created in November 2002 to lead and coordinate the largest reorganization of the U.S. federal government since the consolidation of the armed forces into the Department of Defense.[citation needed]

The Justice Department launched the National Security Entry-Exit Registration System for certain male non-citizens in the U.S., requiring them to register in person at offices of the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

The USA PATRIOT Act of October 2001 dramatically reduces restrictions on law enforcement agencies' ability to search telephone, e-mail communications, medical, financial, and other records; eases restrictions on foreign intelligence gathering within the United States; expands the Secretary of the Treasury's authority to regulate financial transactions, particularly those involving foreign individuals and entities; and broadens the discretion of law enforcement and immigration authorities in detaining and deporting immigrants suspected of terrorism-related acts. The act also expanded the definition of terrorism to include domestic terrorism, thus enlarging the number of activities to which the USA PATRIOT Act's expanded law enforcement powers could be applied. A new Terrorist Finance Tracking Program monitored the movements of terrorists' financial resources (discontinued after being revealed by The New York Times). Global telecommunication usage, including those with no links to terrorism,[230] is being collected and monitored through the NSA electronic surveillance program. The Patriot Act is still in effect.

Political interest groups have stated that these laws remove important restrictions on governmental authority, and are a dangerous encroachment on civil liberties, possible unconstitutional violations of the Fourth Amendment. On 30 July 2003, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) filed the first legal challenge against Section 215 of the Patriot Act, claiming that it allows the FBI to violate a citizen's First Amendment rights, Fourth Amendment rights, and right to due process, by granting the government the right to search a person's business, bookstore, and library records in a terrorist investigation, without disclosing to the individual that records were being searched.[231] Also, governing bodies in many communities have passed symbolic resolutions against the act.

In a speech on 9 June 2005, Bush said that the USA PATRIOT Act had been used to bring charges against more than 400 suspects, more than half of whom had been convicted. Meanwhile, the ACLU quoted Justice Department figures showing that 7,000 people have complained of abuse of the Act.

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) began an initiative in early 2002 with the creation of the Total Information Awareness program, designed to promote information technologies that could be used in counter-terrorism. This program, facing criticism, has since been defunded by Congress.

By 2003, 12 major conventions and protocols were designed to combat terrorism. These were adopted and ratified by many states. These conventions require states to co-operate on principal issues regarding unlawful seizure of aircraft, the physical protection of nuclear materials, and the freezing of assets of militant networks.[232]

In 2005, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 1624 concerning incitement to commit acts of terrorism and the obligations of countries to comply with international human rights laws.[233] Although both resolutions require mandatory annual reports on counter-terrorism activities by adopting nations, the United States and Israel have both declined to submit reports. In the same year, the United States Department of Defense and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff issued a planning document, by the name "National Military Strategic Plan for the War on Terrorism", which stated that it constituted the "comprehensive military plan to prosecute the Global War on Terror for the Armed Forces of the United States...including the findings and recommendations of the 9/11 Commission and a rigorous examination with the Department of Defense".

On 9 January 2007, the House of Representatives passed a bill, by a vote of 299–128, enacting many of the recommendations of the 9/11 Commission The bill passed in the U.S. Senate,[234] by a vote of 60–38, on 13 March 2007 and it was signed into law on 3 August 2007 by President Bush. It became Public Law 110-53. In July 2012, U.S. Senate passed a resolution urging that the Haqqani Network be designated a foreign terrorist organization.[235]

The Office of Strategic Influence was secretly created after 9/11 for the purpose of coordinating propaganda efforts but was closed soon after being discovered. The Bush administration implemented the Continuity of Operations Plan (or Continuity of Government) to ensure that U.S. government would be able to continue in catastrophic circumstances.

Since 9/11, extremists made various attempts to attack the United States, with varying levels of organization and skill. For example, vigilant passengers aboard a transatlantic flight prevented Richard Reid, in 2001, and Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, in 2009, from detonating an explosive device.

Other terrorist plots have been stopped by federal agencies using new legal powers and investigative tools, sometimes in cooperation with foreign governments.[citation needed]

Such thwarted attacks include:

The Obama administration has promised the closing of the Guantanamo Bay detention camp, increased the number of troops in Afghanistan, and promised the withdrawal of its forces from Iraq.

Transnational actions

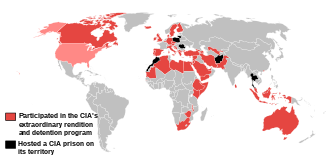

After the September 11 attacks, the United States government commenced a program of illegal "extraordinary rendition," sometimes referred to as "irregular rendition" or "forced rendition," the government-sponsored abduction and extrajudicial transfer of a person from one country to transferee countries, with the consent of transferee countries.[239][240][241] The aim of extraordinary rendition is often conducting torture on the detainee that would be difficult to conduct in the U.S. legal environment, a practice known as torture by proxy. Starting in 2002, U.S. government rendered hundreds of illegal combatants for U.S. detention, and transported detainees to U.S. controlled sites as part of an extensive interrogation program that included torture.[242] Extraordinary rendition continued under the Obama administration; with targets being interrogated and subsequently taken to the US for trial.[243]

The United Nations considers one nation abducting the citizens of another a crime against humanity.[244] In July 2014 the European Court of Human Rights condemned the government of Poland for participating in CIA extraordinary rendition, ordering Poland to pay restitution to men who had been abducted, taken to a CIA black site in Poland, and tortured.[245][246][247]

Rendition to "Black Sites"

In 2005, The Washington Post and Human Rights Watch (HRW) published revelations concerning kidnapping of detainees by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency and their transport to "black sites," covert prisons operated by the CIA whose existence is denied by the US government. The European Parliament published a report connecting use of such secret detention Black Sites for detainees kidnapped as part of extraordinary rendition (See below). Although some Black Sites have been known to exist inside European Union states, these detention centers violate the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and the UN Convention Against Torture, treaties that all EU member states are bound to follow.[248][249][250] The U.S. had ratified the United Nations Convention Against Torture in 1994.[251]

According to ABC News two such facilities, in countries mentioned by Human Rights Watch, have been closed following the recent publicity with the CIA relocating the detainees. Almost all of these detainees were tortured as part of the "enhanced interrogation techniques" of the CIA.[252]

Criticism of American Media's Withholding of Coverage

Major American newspapers, such as "The Washington Post," have been criticized for deliberately withholding publication of articles reporting locations of Black Sites. The Post defended its decision to suppress this news on the ground that such revelations "could open the U.S. government to legal challenges, particularly in foreign courts, and increase the risk of political condemnation at home and abroad." However, according to Fairness and Accuracy In Reporting "the possibility that illegal, unpopular government actions might be disrupted is not a consequence to be feared, however—it's the whole point of the U.S. First Amendment. ... Without the basic fact of where these prisons are, it's difficult if not impossible for 'legal challenges' or 'political condemnation' to force them to close." FAIR argued that the damage done to the global reputation of the United States by the continued existence of black-site prisons was more dangerous than any threat caused by the exposure of their locations.[253]

The complex at Stare Kiejkuty, a Soviet-era compound once used by German intelligence in World War II, is best known as having been the only Russian intelligence training school to operate outside the Soviet Union. Its prominence in the Soviet era suggests that it may have been the facility first identified—but never named—when the Washington Post's Dana Priest revealed the existence of the CIA's secret prison network in November 2005.[254]

The journalists who exposed this provided their sources and this information and documents were provided to The Washington Post in 2005. In addition, they also identified such Black Sites are concealed:

Former European and US intelligence officials indicate that the secret prisons across the European Union, first identified by the Washington Post, are likely not permanent locations, making them difficult to identify and locate.

What some believe was a network of secret prisons was most probably a series of facilities used temporarily by the United States when needed, officials say. Interim "black sites"—secret facilities used for covert activities—can be as small as a room in a government building, which only becomes a black site when a prisoner is brought in for short-term detainment and interrogation.

The journalists went on to explain that "Such a site, sources say, would have to be near an airport." The airport in question is the Szczytno-Szymany International Airport.

In response to these allegations, former Polish intelligence chief, Zbigniew Siemiatkowski, embarked on a media blitz and claimed that the allegations were "... part of the domestic political battle in the US over who is to succeed current Republican President George W Bush," according to the German news agency Deutsche Presse Agentur."[255]

Prison ships

The United States has also been accused of operating "floating prisons" to house and transport those arrested in its War on Terroraccording to human rights lawyers. They have claimed that the US has tried to conceal the numbers and whereabouts of detainees. Although no credible information to support these assertions has ever come to light, the alleged justification for prison ships is primarily to remove the ability for jihadists to target a fixed location to facilitate the escape of high value targets, commanders, operations chiefs etc.[256]

Guantanamo Bay detention camp

The U.S. government set up the Guantanamo Bay detention camp in 2002, a United States military prison located in Guantanamo Bay Naval Base.[257] President Bush declared that the Geneva Convention, a treaty ratified by the U.S. and therefore among the highest law of the land, which protects prisoners of war, would not apply to Taliban and al Qaida detainees captured in Afghanistan.[258] Since inmates were detained indefinitely without trial and several detainees have allegedly been tortured, this camp is considered to be a major breach of human rights by Amnesty International.[259] The detention camp was set up by the U.S. government on Guantanamo Bay since the military base is arguably not legally domestic US territory and thus was a "legal black hole."[260][261] Most prisoners of Guantanamo were eventually freed without ever being charged with any crime, and were transferred to other countries.[262]

Casualties

According to Joshua Goldstein, an international relations professor at the American University, The Global War on Terror has seen fewer war deaths than any other decade in the past century.[263]

There is no widely agreed on figure for the number of people that have been killed so far in the War on Terror as it has been defined by the Bush Administration to include the war in Afghanistan, the war in Iraq, and operations elsewhere. The International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War and the Physicians for Social Responsibility and Physicians for Global Survival give total estimates ranging from 1.3 million to 2 million casualties.[264] Another study from 2018 by Brown University's Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs puts the total number of casualties of the War on Terror in Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan between 480,000 and 507,000.[265] Some estimates for regional conflicts include the following:

- Iraq: 62,570 to 1,124,000

- Iraq Body Count project documented 110,937–121,227 civilian deaths from violence from March 2003 to December 2012.[266][267][268]

- 110,600 deaths in total according to the Associated Press from March 2003 to April 2009.[269]

- 151,000 deaths in total according to the Iraq Family Health Survey.[270]

- Opinion Research Business (ORB) poll conducted 12–19 August 2007 estimated 1,033,000 violent deaths due to the Iraq War. The range given was 946,000 to 1,120,000 deaths. A nationally representative sample of approximately 2,000 Iraqi adults answered whether any members of their household (living under their roof) were killed due to the Iraq War. 22% of the respondents had lost one or more household members. ORB reported that "48% died from a gunshot wound, 20% from the impact of a car bomb, 9% from aerial bombardment, 6% as a result of an accident and 6% from another blast/ordnance."[271][272][273]

- Between 392,979 and 942,636 estimated Iraqi (655,000 with a confidence interval of 95%), civilian and combatant, according to the second Lancet survey of mortality.

- A minimum of 62,570 civilian deaths reported in the mass media up to 28 April 2007 according to Iraq Body Count project.[274]

- 4,409 U.S. military dead (929 non-hostile deaths), and 31,926 wounded in action during Operation Iraqi Freedom.[275] 66 U.S. Military Dead (28 non-hostile deaths), and 295 wounded in action during Operation New Dawn.[275]

- Afghanistan: between 10,960 and 249,000[276]

- According to Marc W. Herold's extensive database,[278] between 3,100 and 3,600 civilians were directly killed by U.S. Operation Enduring Freedom bombing and Special Forces attacks between 7 October 2001 and 3 June 2003. This estimate counts only "impact deaths"—deaths that occurred in the immediate aftermath of an explosion or shooting—and does not count deaths that occurred later as a result of injuries sustained, or deaths that occurred as an indirect consequence of the U.S. airstrikes and invasion.

- In a pair of January 2002 studies, Carl Conetta of the Project on Defense Alternatives estimates that "at least" 4,200–4,500 civilians were killed by mid-January 2002 as a result of the war and Coalition airstrikes, both directly as casualties of the aerial bombing campaign, and indirectly in the resulting humanitarian crisis.

- His first study, "Operation Enduring Freedom: Why a Higher Rate of Civilian Bombing Casualties?",[281] released 18 January 2002, estimates that, at the low end, "at least" 1,000–1,300 civilians were directly killed in the aerial bombing campaign in just the three months between 7 October 2001 to 1 January 2002. The author found it impossible to provide an upper-end estimate to direct civilian casualties from the Operation Enduring Freedom bombing campaign that he noted as having an increased use of cluster bombs.[282] In this lower-end estimate, only Western press sources were used for hard numbers, while heavy "reduction factors" were applied to Afghan government reports so that their estimates were reduced by as much as 75%.[283]

- In his companion study, "Strange Victory: A critical appraisal of Operation Enduring Freedom and the Afghanistan war",[284] released 30 January 2002, Conetta estimates that "at least" 3,200 more Afghans died by mid-January 2002, of "starvation, exposure, associated illnesses, or injury sustained while in flight from war zones", as a result of the war and Coalition airstrikes.

- In similar numbers, a Los Angeles Times review of U.S., British, and Pakistani newspapers and international wire services found that between 1,067 and 1,201 direct civilian deaths were reported by those news organizations during the five months from 7 October 2001 to 28 February 2002. This review excluded all civilian deaths in Afghanistan that did not get reported by U.S., British, or Pakistani news, excluded 497 deaths that did get reported in U.S., British, and Pakistani news but that were not specifically identified as civilian or military, and excluded 754 civilian deaths that were reported by the Taliban but not independently confirmed.[285]

- 2,046 U.S. military dead (339 non-hostile deaths), and 18,201 wounded in action.[275]

- Pakistan: Between 1467 and 2334 people were killed in U.S. drone attacks as of 6 May 2011. Tens of thousands have been killed by terrorist attacks, millions displaced.

- In December 2007, The Elman Peace and Human Rights Organization said it had verified 6,500 civilian deaths, 8,516 people wounded, and 1.5 million displaced from homes in Mogadishu alone during the year 2007.[287]

Total American casualties from the War on Terror

(this includes fighting throughout the world):[291][292][293][294][295]

| | |

|---|---|

| U.S. military killed | 7,008[275] |

| U.S. military wounded | 50,422[275] |

| U.S. DoD civilians killed | 16[275] |

| U.S. civilians killed (includes 9/11 and after) | 3,000 + |

| U.S. civilians wounded/injured | 6,000 + |

| Total Americans killed (military and civilian) | 10,008 + |

| Total Americans wounded/injured | 56,422 + |

The United States Department of Veterans Affairs has diagnosed more than 200,000 American veterans with PTSD since 2001.[296]

Total terrorist casualties

On December 7, 2015, the Washington Post reported that since 2001, in five theaters of the war (Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, Syria and Somalia) that the total number of terrorists killed ranges from 65,800 to 88,600, with the Obama administration being responsible for between 30,000 and 33,000.[297]

Costs

The War on Terror, spanning decades, is a multitrillion-dollar war.

According to the Costs of War Project at Brown University's Watson Institute, the War on Terror will have cost $5.6 trillion for operations between 2001-2018 plus anticipated future costs of veterans' care.[298]

According to the Soufan Group in July 2015, the U.S. government was spending $9.4 million per day in operations against ISIS in Syria and Iraq.[299]

A March 2011 Congressional report[300] estimated war spending through the fiscal year 2011 at $1.2 trillion, and future spending through 2021 (assuming a reduction to 45,000 troops) at $1.8 trillion. A June 2011 academic report[300] covering additional areas of war spending estimated it through 2011 at $2.7 trillion, and long-term spending at $5.4 trillion including interest.[note 5]

| Expense | CRS/CBO (billions US$):[301][302][303] | Watson (billions constant US$):[304] |

|---|---|---|

| FY2001–FY2011 | ||

| War appropriations to DoD | 1208.1 | 1311.5 |

| War appropriations to DoS/USAID | 66.7 | 74.2 |

| VA Medical | 8.4 | 13.7 |

| VA disability | 18.9 | |

| Interest paid on DoD war appropriations | 185.4 | |

| Additions to DoD base spending | 362.2–652.4 | |

| Additions to Homeland Security base spending | 401.2 | |

| Social costs to veterans and military families to date | 295–400 | |

| Subtotal: | 1,283.2 | 2,662.1–3,057.3 |

| FY2012–future | ||

| FY2012 DoD request | 118.4 | |

| FY2012 DoS/USAID request | 12.1 | |

| Projected 2013–2015 war spending | 168.6 | |

| Projected 2016–2020 war spending | 155 | |

| Projected obligations for veterans' care to 2051 | 589–934 | |

| Additional interest payments to 2020 | 1,000 | |

| Subtotal: | 454.1 | 2043.1–2388.1 |

| Total: | 1737.3 | 4705.2–5445.4 |

Criticism