Form der Literatur

Poesie (der Begriff leitet sich von einer Variante des griechischen Begriffs ab, poiesis "Making") ist eine Form der Literatur, die ästhetisch und rhythmisch verwendet [1][2][3] . Sprachqualitäten - wie Phonästhetik, Klangsymbolik und Messinstrument -, um zusätzlich oder anstelle der prosaischen scheinbaren Bedeutung Bedeutungen hervorzurufen.

Poesie hat eine sehr lange Geschichte, die bis in die Urzeit mit der Entstehung von Jagdpoesie in Afrika zurückreicht. Panegyrische und elegische Hofpoesie wurde im Laufe der Geschichte der Reiche des Nils, des Niger und der Volta-Täler ausgiebig entwickelt [19659005]. Einige der ältesten schriftlichen Gedichte in Afrika sind unter den Pyramidentexten aus dem 25. Jahrhundert v. Chr. Zu finden, während das Epi von Sundiata eines der bekanntesten Beispiele für Griot-Court-Poesie ist. Das früheste westasiatische Epos, das Gilgamesch-Epos wurde auf Sumerisch geschrieben. Frühe Gedichte auf dem eurasischen Kontinent entwickelten sich aus Volksliedern wie dem chinesischen Shijing oder aus dem Bedürfnis, orale Epen nacherzählen, wie bei den Sanskrit Vedas Zoroastrian Gathas ] und die homerischen Epen, die Ilias und die Odyssey . Antike griechische Versuche, die Poesie zu definieren, wie etwa die Poetik von Aristoteles konzentrierten sich auf die Verwendung von Sprache in Rhetorik, Drama, Lied und Komödie. Spätere Versuche konzentrierten sich auf Merkmale wie Wiederholung, Versform und Reim und betonten die Ästhetik, die die Poesie von objektiv informativeren, prosaischen Schreibweisen unterscheidet.

Poesie verwendet Formen und Konventionen, um unterschiedliche Interpretationen von Wörtern vorzuschlagen oder um emotionale Reaktionen hervorzurufen. Geräte wie Assonanz, Alliteration, Onomatopoeie und Rhythmus werden manchmal verwendet, um musikalische oder beschwörende Wirkungen zu erzielen. Die Verwendung von Zweideutigkeit, Symbolik, Ironie und anderen Stilelementen der poetischen Diktion lässt ein Gedicht häufig für mehrere Interpretationen offen. In ähnlicher Weise erzeugen Sprachfiguren wie Metapher, Gleichnis und Metonymie [5] eine Resonanz zwischen ansonsten unterschiedlichen Bildern - einer Schichtung von Bedeutungen, die Verbindungen bilden, die zuvor nicht wahrgenommen wurden. Verwandten Formen der Resonanz können zwischen einzelnen Versen in ihren Mustern von Reim oder Rhythmus existieren.

Einige Poesietypen sind spezifisch für bestimmte Kulturen und Gattungen und reagieren auf Merkmale der Sprache, in der der Dichter schreibt. Leser, die daran gewöhnt sind, Gedichte mit Dante, Goethe, Mickiewicz und Rumi zu identifizieren, denken vielleicht, dass sie in Zeilen geschrieben sind, die auf Reim und normalem Meter basieren. Es gibt jedoch Traditionen wie die biblische Poesie, die andere Mittel verwenden, um Rhythmus und Euphonie zu erzeugen. Viele moderne Gedichte spiegeln eine Kritik der poetischen Tradition wider [6] indem sie mit dem Prinzip der Euphonie selbst spielen und sie testen, wobei sie manchmal ganz auf den Reim oder den festgelegten Rhythmus verzichten. [7][8] In der zunehmend globalisierten Welt der heutigen Zeit ändern Dichter häufig Formen, Stile und Techniken aus verschiedenen Kulturen und Sprachen.

Geschichte [ edit ]

Einige Gelehrte glauben, dass die Kunst der Poesie vor der Alphabetisierung bestehen kann. [9] Andere legen jedoch nahe, dass die Poesie nicht zwangsläufig vor dem Schreiben war. [10]

Die älteste Das überlebende Gedicht, das Epos von Gilgamesh stammt aus dem 3. Jahrtausend v. Chr. in Sumer (in Mesopotamien, jetzt Irak) und wurde in Keilschrift auf Tontafeln und später geschrieben. auf Papyrus. [11] Eine Tablette aus der Zeit von ca. 2000 BCE beschreibt einen jährlichen Ritus, in dem der König symbolisch mit der Göttin Inanna heiratete und sich paarte, um Fruchtbarkeit und Wohlstand sicherzustellen; es gilt als das älteste Liebesgedicht der Welt. [12][13] Ein Beispiel ägyptischer Epos ist Die Geschichte von Sinuhe (ca. 1800 v. Chr.).

behandelt die griechischen Epen, die Ilias und die Odyssee ; die avestanischen Bücher, die Gathic Avesta und die Yasna ; das römische Nationalepos, Vergil (19459010) Aeneid (19459011); und die indischen Epen, der Ramayana und der Mahabharata . Epische Gedichte, darunter die Odyssey die Gathas von 19459011 und die indischen Vedas scheinen in poetischer Form als Hilfsmittel zur Erinnerung und mündlichen Übertragung komponiert worden zu sein. in prähistorischen und antiken Gesellschaften. [10] [14]

Andere Formen der Poesie entwickelten sich direkt aus Volksliedern. Die ältesten Einträge in der ältesten noch existierenden Sammlung chinesischer Gedichte, Shijing waren anfangs die Texte. [15]

Die Bemühungen der antiken Denker zu bestimmen, was Poesie als unverwechselbar macht Form, und was gute Poesie von schlecht unterscheidet, führte zu "Poetik" - dem Studium der Ästhetik der Poesie. [16] Einige alte Gesellschaften, wie Chinas durch sie Shijing (Classic of Poetry) ) entwickelte Kanons von poetischen Werken, die sowohl rituelle als auch ästhetische Bedeutung hatten. [17] In jüngster Zeit haben Denker Mühe gehabt, eine Definition zu finden, die sowohl formale Unterschiede als auch die zwischen Chaucers Canterbury Tales umfassen könnte ] und Matsuo Bashōs Oku no Hosomichi sowie inhaltliche Unterschiede zwischen religiösen Tanakh-Gedichten, Liebesgedichten und Rap. [18]

Westliche Traditionen [ edit

] Klassische Denker Mitarbeiter oyed-Klassifizierung als Weg zur Definition und Bewertung der Qualität von Poesie. Insbesondere beschreiben die vorhandenen Fragmente von Aristoteles Poetics drei Arten von Poesie - das Epos, das Komische und das Tragische - und entwickeln Regeln zur Unterscheidung der qualitativ besten Dichtung in jedem Genre, basierend auf den zugrunde liegenden Zwecken das Genre. [19] Spätere Ästhetiker identifizierten drei Hauptgattungen: epische Poesie, lyrische Poesie und dramatische Poesie, wobei Komödien und Tragödien als Subgenres dramatischer Poesie behandelt wurden. [20]

Aristoteles 'Arbeit war durchgehend einflussreich im Nahen Osten während des islamischen Goldenen Zeitalters [21] sowie in Europa während der Renaissance. [22] Spätere Dichter und Ästhetiker unterschieden häufig die Poesie von und definierten sie im Gegensatz zur Prosa, die im Allgemeinen als Schreiben mit einer Neigung verstanden wurde zu logischen Erklärungen und einer linearen narrativen Struktur. [23]

Dies bedeutet nicht, dass Dichtung unlogisch ist oder dass ihnen Erzählung fehlt, sondern dass Dichtung ein Versuch ist, zu rendern das Schöne oder Erhabene ohne die Last, den logischen oder narrativen Denkprozess zu betreiben. Der englische romantische Dichter John Keats nannte diese Flucht vor der Logik "Negative Capability". [24] Dieser "romantische" Ansatz betrachtet Form als Schlüsselelement erfolgreicher Poesie, da Form abstrakt und von der zugrunde liegenden Begriffslogik verschieden ist. Dieser Ansatz blieb bis ins 20. Jahrhundert einflussreich. [25]

In dieser Zeit gab es auch wesentlich mehr Wechselwirkungen zwischen den verschiedenen poetischen Traditionen, teilweise aufgrund der Verbreitung des europäischen Kolonialismus und des damit einhergehenden Aufstiegs im Welthandel. [26] Neben einem Übersetzungsboom wurden in der Romantik zahlreiche antike Werke wiederentdeckt. [27]

Streitfälle aus dem 20. Jahrhundert und dem 21. Jahrhundert [ ] Einige Literaturtheoretiker des 20. Jahrhunderts, die sich weniger auf den Widerstand von Prosa und Poesie stützten, konzentrierten sich auf den Dichter als einfach einen, der unter Verwendung von Sprache und Poesie als das, was der Dichter schafft, [28] das zugrunde liegende Konzept des Dichters als Schöpfer ist nicht ungewöhnlich, und einige modernistische Dichter unterscheiden im Wesentlichen nicht zwischen der Erstellung eines Gedichtes mit Worten und kreativen Handlungen in anderen Medien. Wieder andere Modernisten fordern den Versuch, die Dichtung als falsch zu definieren, in Frage zu stellen: 19459063 [29] Die Ablehnung traditioneller Formen und Strukturen für die Dichtung, die in der ersten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts begann, fiel mit einer Befragung des Zweck und Bedeutung traditioneller Definitionen von Dichtung und von Unterschieden zwischen Dichtung und Prosa, insbesondere gegebene Beispiele für poetische Prosa und prosaische Dichtung. Zahlreiche modernistische Dichter haben in nicht-traditionellen Formen oder in etwas geschrieben, was traditionell als Prosa angesehen worden wäre, obwohl ihr Schreiben im Allgemeinen mit poetischer Diktion und oft mit Rhythmus und Ton versehen wurde, die durch nicht-metrische Mittel festgelegt wurden. Während in den modernistischen Schulen eine erhebliche formalistische Reaktion auf den Zusammenbruch der Struktur stattfand, konzentrierte sich diese Reaktion ebenso auf die Entwicklung neuer formaler Strukturen und Synthesen wie auf die Wiederbelebung älterer Formen und Strukturen. [30]

In letzter Zeit hat Postmodernismus Pros und Poesie als eigenständige Entitäten und auch unter den Gattungen der Poesie vollständiger vermittelt, da sie nur als kulturelle Artefakte von Bedeutung sind. Postmodernismus geht über die Betonung des Modernismus hinaus auf die schöpferische Rolle des Dichters, um die Rolle des Lesers eines Textes (Hermeneutik) zu betonen und das komplexe kulturelle Netz hervorzuheben, in dem ein Gedicht gelesen wird. Heute, auf der ganzen Welt, Poesie enthält oft poetische Formen und Ausdrucksweisen aus anderen Kulturen und aus der Vergangenheit, weitere verwirrende Definitions- und Einstufungsversuche, die einst in einer Tradition wie dem westlichen Kanon vernünftig waren. [32]

Anfang des 21. Jahrhunderts Die poetische Tradition des Jahrhunderts scheint sich weiterhin stark an früheren poetischen Vorläufertraditionen zu orientieren, wie sie von Whitman, Emerson und Wordsworth initiiert wurden. Der Literaturkritiker Geoffrey Hartman hat den Ausdruck "Die Angst der Nachfrage" verwendet, um die zeitgenössische Antwort auf ältere poetische Traditionen als "Angst vor der Tatsache, dass die Tatsache keine Form mehr hat" zu beschreiben, aufbauend auf einem von Emerson eingeführten Trope. Emerson hatte behauptet, in der Debatte über die poetische Struktur, wo entweder "Form" oder "Fakt" vorherrschen könne, müsse man einfach "Frag die Tatsache nach der Form". Dies wurde auf verschiedenen Ebenen von anderen Literaturwissenschaftlern wie Bloom angezweifelt, der in zusammenfassender Form zu Beginn des 21. Jahrhunderts Folgendes feststellte: "Die Generation der Dichter, die jetzt zusammenstehen, ist reif und bereit, die großen amerikanischen Verse der zwanziger Jahre zu schreiben. Das erste Jahrhundert kann noch als das angesehen werden, was Stevens als "die letzte Verschönerung eines großen Schattens" bezeichnet hat, der Schatten ist Emersons. "[33]

Elements [ edit ]

Prosody [ [ edit ]

Prosody ist das Studium des Meters, des Rhythmus und der Intonation eines Gedichts. Rhythmus und Meter sind unterschiedlich, obwohl eng verwandt. [34] Meter ist das definitive Muster, das für einen Vers (wie etwa Iambikpentameter) festgelegt wurde, während Rhythmus der tatsächliche Klang ist, der sich aus einer Reihe von Gedichten ergibt. Prosody kann auch spezifischer verwendet werden, um sich auf das Scannen von poetischen Linien zu beziehen, um Meter darzustellen. [35]

Rhythm [ edit ]

Die Methoden zur Erzeugung poetischer Rhythmen variieren zwischen den Sprachen und zwischen den poetischen Traditionen. Es wird oft beschrieben, dass Sprachen über ein Timing verfügen, das in erster Linie durch Akzente, Silben oder Moras festgelegt wird, je nachdem, wie der Rhythmus festgelegt ist. Eine Sprache kann jedoch durch mehrere Ansätze beeinflusst werden. Japanisch ist eine mora-time Sprache. Latein, Katalanisch, Französisch, Leonisch, Galizisch und Spanisch werden als Silbensprache bezeichnet. Stresssimulierte Sprachen umfassen Englisch, Russisch und allgemein Deutsch. [36] Unterschiedliche Intonation beeinflusst auch die Wahrnehmung von Rhythmus. Sprachen können sich entweder auf Tonhöhe oder Tonhöhe verlassen. Einige Sprachen mit einem Pitch-Akzent sind Vedic Sanskrit oder Altgriechisch. Zu den Tonsprachen zählen Chinesisch, Vietnamesisch und die meisten Subsaharan-Sprachen. [37]

Der metrische Rhythmus umfasst im Allgemeinen präzise Anordnungen von Spannungen oder Silben zu sich wiederholenden Mustern, die als Fuß innerhalb einer Linie bezeichnet werden. In den Versen der modernen englischen Sprache unterscheidet das Spannungsmuster in erster Linie die Füße, so dass der Rhythmus, der sich auf das moderne Englisch bezieht, meistens auf das Muster der gestressten und unbelasteten Silben (allein oder abgelenkt) basiert. [38] In den klassischen Sprachen dagegen Während die metrischen Einheiten ähnlich sind, definieren Vokallänge statt Spannungen den Zähler. [39] Die alte englische Dichtung verwendete ein metrisches Muster, bei dem eine unterschiedliche Anzahl von Silben, aber eine feste Anzahl von starken Spannungen in jeder Zeile vorlag. [40]

Die alte hebräische biblische Dichtung, zu der viele der Psalmen gehörten, war Parallelismus eine rhetorische Struktur, in der sich aufeinanderfolgende Zeilen in grammatischer Struktur, Klangstruktur, fiktionalem Inhalt oder in allen drei Bereichen widerspiegelten. Parallelismus bot sich für eine antiphonale oder Call-and-Response-Performance an, die auch durch Intonation verstärkt werden könnte. Die biblische Poesie verlässt sich daher weniger auf metrische Füße, um Rhythmus zu erzeugen, sondern erzeugt Rhythmus, der auf viel größeren Klangeinheiten von Linien, Phrasen und Sätzen beruht. [41] Einige klassische Poesieformen, wie beispielsweise Venpa der tamilischen Sprache, hatten starre Grammatiken (bis zu dem Punkt, dass sie als kontextfreie Grammatik ausgedrückt werden könnten), der für einen Rhythmus sorgte. [42]

Die klassische chinesische Poetik, basierend auf dem Tonsystem des mittleren Chinesen, erkannte zwei Arten von Töne: der Pegel (平 píng ) und der schräge (仄 zè ) Ton, eine Kategorie, die aus dem aufsteigenden (上 sháng ) Ton besteht, der Abgang (1945 qù ) Ton und der eintretende (入 rù ) Ton. Bestimmte Formen der Dichtung stellten Beschränkungen auf, zu denen Silben eben und welche schräg sein mussten.

Die in modernen englischen Versen verwendeten Rhythmusmuster zur Erzeugung von Rhythmus dominieren nicht mehr die zeitgenössische englische Poesie. Im Fall des freien Verses wird der Rhythmus oft auf der Basis loser Trittfrequenzeinheiten statt eines normalen Takts organisiert. Robinson Jeffers, Marianne Moore und William Carlos Williams sind drei bemerkenswerte Dichter, die die Vorstellung ablehnen, dass reguläre Akzentanzeigen für die englische Dichtung von entscheidender Bedeutung sind. [43] Jeffers experimentierte mit dem gefederten Rhythmus als Alternative zum Akzentrhythmus. [1965962] Meter

[ edit ]

In der westlichen poetischen Tradition werden Messgeräte üblicherweise nach einem charakteristischen metrischen Fuß und der Anzahl der Fuß pro Linie gruppiert. [46] Die Anzahl der metrischen Füße in einer Zeile wird anhand von beschrieben Griechische Terminologie: Tetrameter für vier Fuß und Hexameter für sechs Fuß. [47] So ist "Iambic Pentameter" ein Meter mit fünf Fuß pro Zeile, in dem die vorherrschende Fußart der "Iamb" ist. Dieses metrische System stammt aus der antiken griechischen Dichtung und wurde von Dichtern wie Pindar und Sappho sowie von den großen Tragödiern von Athen verwendet. In ähnlicher Weise umfasst "Dactylhexameter" sechs Fuß pro Linie, von denen die dominierende Art des Fußes "Dactyl" ist. Dactylisches Hexameter war das traditionelle Messinstrument der griechischen Epik, deren älteste Beispiele die Werke von Homer und Hesiod sind. [48] Iambisches Pentameter und Dactylisches Hexameter wurden später von einer Reihe von Dichtern verwendet, darunter William Shakespeare und Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. [49] Die gebräuchlichsten metrischen Füße in englischer Sprache sind: [50]

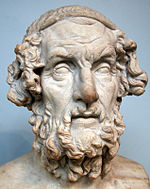

Homer: Römische Büste, basierend auf griechischem [i0659070] Iamb - eine unbelastete Silbe, gefolgt von einer gestressten Silbe (z. B. cribe ) clude re tract )

Homer: Römische Büste, basierend auf griechischem [i0659070] Iamb - eine unbelastete Silbe, gefolgt von einer gestressten Silbe (z. B. cribe ) clude re tract )

trochee - eine betonte Silbe, gefolgt von einer unbelasteten Silbe (z. B. pic -Folge, ) -er)

Dactyl - eine gestresste Silbe, gefolgt von zwei unbelasteten Silben (z. B. und -nate, sim -i-lar)

. zwei unbelastete Silben, gefolgt von einer betonten Silbe (z. B. com-pre- hend ) [1965907] 1] Spondee - zwei gestresste Silben zusammen (z. heart - beat four - teen )

pyrrhic - zwei unbelastete Silben zusammen (selten, normalerweise zum Beenden dactylischer Hexameter ) Es gibt eine breite Palette von Namen für andere Fußtypen, bis hin zu einem Choriamb, einem viersilbigen metrischen Fuß mit einer betonten Silbe, gefolgt von zwei unbelasteten Silben und dem Schließen mit einer gestressten Silbe. Der Choriamb stammt aus einigen alten griechischen und lateinischen Gedichten. [48] Sprachen, die Vokallänge oder Intonation anstelle von oder zusätzlich zu silabischen Akzenten, wie osmanisches Türkisch oder Vedisch, verwenden, haben oft ähnliche Konzepte wie Iamb und Dactyl um gewöhnliche Kombinationen von langen und kurzen Klängen zu beschreiben. [52]

Jeder dieser Fußtypen hat ein gewisses "Gefühl", entweder allein oder in Kombination mit anderen Füßen. Das Iamb zum Beispiel ist die natürlichste Form des Rhythmus in der englischen Sprache und erzeugt im Allgemeinen einen subtilen, aber stabilen Vers. [53] Der Scanning-Meter kann oft das grundlegende oder grundlegende Muster eines Verses zeigen, zeigt jedoch nicht das Variieren Stress, sowie die unterschiedlichen Tonhöhen und Längen der Silben. [54]

Es gibt Debatten darüber, wie nützlich eine Vielzahl unterschiedlicher "Füße" bei der Beschreibung von Metern ist. Zum Beispiel hat Robert Pinsky argumentiert, dass, während Dactyle in klassischen Versen wichtig sind, englische Dactylverse Dactyle sehr unregelmäßig verwenden und basierend auf Mustern von Iambs und Anapests, Füßen, die er für die Sprache als natürlich betrachtet, besser beschrieben werden können. [55] Actual Rhythmus ist wesentlich komplexer als das oben beschriebene grundlegende abgetastete Messgerät, und viele Wissenschaftler haben versucht, Systeme zu entwickeln, die eine solche Komplexität scannen. Vladimir Nabokov wies darauf hin, dass das reguläre Muster der gestressten und unbelasteten Silben in einer Verszeile ein separates Muster von Akzenten ist, das sich aus der natürlichen Tonhöhe der gesprochenen Wörter ergibt, und schlug vor, den Ausdruck "scud" zur Unterscheidung eines Wortes zu verwenden unakzentuierter Stress durch einen betonten Stress. [56]

Metrische Muster [ edit ]

Unterschiedliche Traditionen und Gattungen der Poesie verwenden unterschiedliche Messinstrumente, die vom Shakespearean-Iambus-Pentameter bis zum homerischen dactylischen Hexameter reichen zu dem anapestischen Tetrameter, der in vielen Kinderreimen verwendet wird. Es gibt jedoch eine Reihe von Variationen des etablierten Messgeräts, um sowohl einen bestimmten Fuß oder eine Linie hervorzuheben oder zu betonen und langweilige Wiederholungen zu vermeiden. Zum Beispiel kann die Belastung eines Fußes umgekehrt werden, eine Zäsur (oder Pause) kann hinzugefügt werden (manchmal anstelle eines Fußes oder einer Belastung), oder der letzte Fuß in einer Linie kann ein weibliches Ende erhalten, um ihn weich zu machen oder zu sein durch einen spondee ersetzt, um es zu betonen und einen harten stop zu schaffen. Einige Muster (wie z. B. Iambuspentameter) sind in der Regel recht regelmäßig, während andere Muster, z. B. Dactylhexameter, sehr unregelmäßig sind. [57] Die Regelmäßigkeit kann je nach Sprache variieren. Darüber hinaus entwickeln sich unterschiedliche Muster häufig in verschiedenen Sprachen deutlich, so dass beispielsweise Iambic-Tetrameter in Russisch im Allgemeinen eine Regelmäßigkeit der Verwendung von Akzenten zur Verstärkung des Messgeräts widerspiegelt, die nicht auftritt oder in viel geringerem Maße auftritt. auf Englisch. [58]

Einige gängige metrische Muster mit bemerkenswerten Beispielen von Dichtern und Gedichten, die sie verwenden, sind:

- Iambischer Pentameter (John Milton, Paradise Lost ; William Shakespeare, Sonette )

- Dactylischer Hexameter (Homer, ) Iliad ; Virgil, Aeneid ) [60]

- Iambischer Tetrameter (Andrew Marvell, "An seine Coy-Mistress"; Alexander Pushkin, Eugene Onegin ) Robert Frost, Zwischen Wald an einem verschneiten Abend ) [61]

- Trochaischer Oktameter (Edgar Allan Poe, "Der Rabe") [62] [62] [62] ]

- Trochaic Tetrameter (Henry Wadsworth Longfellow) "Das Lied von Hiawatha"; Das finnische nationale Epos "Kalevala" ist auch in trochaischem Tetrameter, dem natürlichen Rhythmus von Finnisch und Estnisch.

- Alexandrine (Jean Racine, Phèdre ) [63]

Rhyme, Alliteration, Assonance [ edit ]

Reim, Alliteration, Assonanz und Konsonanz sind Möglichkeiten, sich wiederholende Klangmuster zu erzeugen. Sie können als eigenständiges Strukturelement in einem Gedicht, zur Verstärkung rhythmischer Muster oder als dekoratives Element verwendet werden. [64] Sie können auch eine von den sich wiederholenden Klangmustern getrennte Bedeutung haben. Beispielsweise benutzte Chaucer schwere Alliterationen, um Old English Verse zu verspotten und eine Figur als archaisch zu malen. [65]

Der Reim besteht aus einem identischen ("harten Reim") oder einem ähnlichen ("weichen Reim") ") Klänge, die an den Zeilenenden oder an vorhersagbaren Stellen innerhalb der Zeilen platziert werden (" interner Reim "). Sprachen variieren im Reichtum ihrer gereimten Strukturen; Italienisch hat zum Beispiel eine reiche Reimstruktur, die die Aufrechterhaltung einer begrenzten Anzahl von Reimen in einem langen Gedicht erlaubt. Der Reichtum ergibt sich aus Wortendungen, die regelmäßigen Formen folgen. Englisch ist mit seinen unregelmäßigen Wortendungen aus anderen Sprachen weniger reimreich. [66] Der Reichtum der Reimstrukturen einer Sprache spielt eine wesentliche Rolle bei der Bestimmung, welche poetischen Formen in dieser Sprache häufig verwendet werden. [67]

Alliteration ist die Wiederholung von Buchstaben oder Buchstabentönen am Anfang von zwei oder mehr Wörtern, die unmittelbar aufeinander folgen oder in kurzen Abständen. oder die Wiederholung desselben Buchstabens in akzentuierten Wortteilen. Alliteration und Assonanz spielten eine Schlüsselrolle bei der Strukturierung der frühen germanischen, nordischen und altglischen Formen der Poesie. Die alliterativen Muster der frühgermanischen Poesie verweben Meter und Alliteration als einen wesentlichen Teil ihrer Struktur, so dass das metrische Muster bestimmt, wann der Hörer Vorkommnisse der Alliteration erwartet. Dies ist vergleichbar mit einer ornamentalen Verwendung von Alliteration in den meisten modernen europäischen Gedichten, bei denen Alliterationsmuster nicht formal sind oder durch volle Strophen getragen werden. Alliteration ist besonders nützlich in Sprachen mit weniger reichen Reimstrukturen.

Assonance, bei der die Verwendung ähnlicher Vokaltöne innerhalb eines Wortes anstelle von ähnlichen Tönen am Anfang oder Ende eines Wortes verwendet wurde, wurde in der Skaldischen Poesie häufig verwendet, geht aber auf das homerische Epos zurück. [68] Weil Verben viel davon tragen In der englischen Sprache kann Assonance die tonalen Elemente der chinesischen Poesie locker hervorrufen und ist daher nützlich bei der Übersetzung chinesischer Poesie. [69] Konsonanz tritt auf, wenn ein Konsonantenklang während eines Satzes wiederholt wird, ohne dass der Klang nur an der Vorderseite eines Satzes steht Wort. Konsonanz bewirkt einen subtileren Effekt als Alliteration und ist daher als strukturelles Element weniger nützlich. [67]

Rhyming-Schemen [ edit ]

In vielen Sprachen, einschließlich moderner europäischer Sprachen und arabischer Dichter Verwenden Sie den Reim in Satzmustern als strukturelles Element für bestimmte poetische Formen wie Balladen, Sonette und reimende Couplets. Die Verwendung von Strukturreimen ist jedoch selbst in der europäischen Tradition nicht allgemein. Viele moderne Gedichte vermeiden traditionelle Reimschemata. Die klassische griechische und lateinische Dichtung benutzte keinen Reim. [70] Rhyme trat im Hochmittelalter in europäische Dichtung ein, teilweise unter dem Einfluss der arabischen Sprache in Al Andalus (modernes Spanien). [71] Die arabischsprachigen Dichter verwendeten Reime weitgehend die erste Entwicklung des literarischen Arabisch im sechsten Jahrhundert, wie in ihren langen, reimenden Qasidas. [72] Einige Reimschemata wurden mit einer bestimmten Sprache, Kultur oder Periode verbunden, während andere Reimschemata über Sprachen, Kulturen oder Zeiten hinweg Verwendung fanden Perioden. Einige Formen der Poesie tragen ein einheitliches und genau definiertes Reimschema, wie etwa der Chantal Royale oder der Rubaiyat, während andere Poetikformen variable Reimschemata haben. [73]

Die meisten Reimschemata werden mit beschrieben Buchstaben, die Gruppen von Reimen entsprechen. Wenn also die erste, zweite und vierte Zeile eines Quatrain-Reims miteinander und die dritte Zeile nicht reimt, wird gesagt, dass der Quatrain ein "aa-ba" -Rim-Schema hat. Dieses Reimschema wird beispielsweise in der Rubaiyatform verwendet. [74] In ähnlicher Weise wird ein "a-bb-a" -Quatrain (was als "geschlossener Reim" bezeichnet wird) in solchen Formen wie dem Petrarchanischen Sonett verwendet. [75] Einige Arten komplizierterer Reimschemata haben eigene Namen entwickelt, getrennt von der "a-bc" -Konvention, wie z. B. ottava rima und terza rima. [76] Die Arten und Verwendung unterschiedlicher Reimschemata werden weiter erörtert im Hauptartikel.

Form in der Dichtung [ edit ]

Die poetische Form ist in der modernistischen und postmodernen Poesie flexibler und ist nach wie vor weniger strukturiert als in früheren literarischen Epochen. Viele moderne Dichter meiden erkennbare Strukturen oder Formen und schreiben in freien Versen. Aber die Poesie unterscheidet sich von der Prosa durch ihre Form. Ein gewisser Respekt für grundlegende formale Strukturen der Dichtung wird selbst im besten freien Vers gefunden werden, auch wenn solche Strukturen scheinbar ignoriert wurden. [77] Ebenso wird es in den besten klassischen klassischen Gedichten Abweichungen von der strikten Form geben Hervorhebung oder Wirkung. [78]

Zu den wichtigsten Strukturelementen, die in der Poesie verwendet werden, gehören die Linie, die Strophe oder Versabsatz und größere Kombinationen von Strophen oder Linien wie Cantos. Manchmal werden auch breitere visuelle Darstellungen von Wörtern und Kalligraphie verwendet. Diese Grundeinheiten der poetischen Form werden oft zu größeren Strukturen zusammengefasst, die als poetische Formen oder poetischen Modi (siehe folgenden Abschnitt) bezeichnet werden, wie im Sonett oder Haiku.

Zeilen und Zeilengruppen [ edit ]

Poesie wird oft in Zeilen auf einer Seite unterteilt. Diese Linien können auf der Anzahl der metrischen Füße basieren oder ein Reimmuster an den Enden der Linien betonen. Linien können anderen Funktionen dienen, insbesondere wenn das Gedicht nicht in einem formalen metrischen Muster geschrieben ist. Linien können Gedanken, die in verschiedenen Einheiten ausgedrückt sind, trennen, vergleichen oder kontrastieren oder eine Tonänderung hervorheben. [79] Informationen zur Aufteilung zwischen Zeilen finden Sie im Artikel über Zeilenumbrüche.

Gedichtzeilen sind oft in Strophen angeordnet, die durch die Anzahl der enthaltenen Zeilen bezeichnet werden. Eine Ansammlung von zwei Zeilen ist also ein Couplet (oder Distich), drei Zeilen ein Triplett (oder Tercet), vier Zeilen ein Quatrain und so weiter. Diese Linien können sich durch Rhythmus oder Rhythmus aufeinander beziehen. Zum Beispiel kann ein Couplet zwei Linien mit identischen Takten sein, die sich reimen, oder zwei Linien, die allein durch einen gemeinsamen Meter zusammengehalten werden. [80]

Bloks russisches Gedicht " Noch, ulitsa, fonar, apteka " ("Nacht , Straße, Lampe, Drogerie "), an einer Wand in Leiden

Bloks russisches Gedicht " Noch, ulitsa, fonar, apteka " ("Nacht , Straße, Lampe, Drogerie "), an einer Wand in Leiden

Andere Gedichte können in Versabschnitten organisiert werden, in denen regelmäßige Reime mit etablierten Rhythmen nicht verwendet werden, stattdessen der poetische Ton durch eine Sammlung von Rhythmen festgelegt wird. Alliterationen und Reime in Absatzform festgelegt. [81] Viele Verse aus dem Mittelalter wurden in Versabschnitten geschrieben, auch wenn regelmäßige Reime und Rhythmen verwendet wurden. [82]

In vielen Formen der Poesie gibt es Stanzas Ineinandergreifen, so dass das Reimschema oder andere strukturelle Elemente einer Strophe die der nachfolgenden Strophen bestimmen. Beispiele für solche ineinandergreifenden Strophen umfassen zum Beispiel Ghazal und Villanelle, wobei ein Refrain (oder, im Falle der Villanelle, Refrains) in der ersten Strophe festgelegt wird, die sich dann in nachfolgenden Strophen wiederholt. In Verbindung mit der Verwendung von ineinandergreifenden Strophen ist ihre Verwendung zur Trennung thematischer Teile eines Gedichts. Beispielsweise werden Strophe, Antistrophe und Epode der Odenform häufig in eine oder mehrere Strophen unterteilt. [83]

In einigen Fällen sind besonders längere Formgedichten, wie zum Beispiel einige Formen epischer Poesie, Strophen selbst werden nach strengen Regeln konstruiert und dann kombiniert. In der skaldischen Poesie hatte die Strophe dróttkvætt acht Zeilen mit jeweils drei "Lifts", die mit Alliteration oder Assonanz erzeugt wurden. Zusätzlich zu zwei oder drei Alliterationen hatten die ungeradzahligen Zeilen einen teilweise Reim von Konsonanten mit unterschiedlichen Vokalen, nicht unbedingt am Wortanfang; Die geraden Zeilen enthielten den inneren Reim in bestimmten Silben (nicht unbedingt am Ende des Wortes). Jede halbe Zeile hatte genau sechs Silben und jede Zeile endete in einem Trochee. Die Anordnung der Dróttkvætts folgte weit weniger strengen Regeln als die Konstruktion der einzelnen Dróttkvætts. [84]

Visuelle Präsentation [ edit ]

Selbst vor dem Aufkommen des Drucks war der visuelle Eindruck der Poesie häufig Bedeutung oder Tiefe hinzugefügt. Akrostichon-Gedichte vermittelten Bedeutungen in den Anfangsbuchstaben von Zeilen oder in Buchstaben an anderen spezifischen Stellen in einem Gedicht. [85] In arabischer, hebräischer und chinesischer Poesie hat die visuelle Darstellung fein kalligrafierter Gedichte eine wichtige Rolle in der Gesamtwirkung vieler Gedichte. [86]

Mit dem Aufkommen des Druckens erhielten die Dichter eine größere Kontrolle über die in Massen produzierten visuellen Präsentationen ihrer Arbeit. Visuelle Elemente sind zu einem wichtigen Bestandteil des Werkzeugkastens des Dichters geworden, und viele Dichter haben versucht, die visuelle Präsentation für eine Vielzahl von Zwecken einzusetzen. Einige modernistische Dichter haben die Platzierung einzelner Linien oder Liniengruppen auf der Seite zu einem festen Bestandteil der Komposition des Gedichts gemacht. Manchmal ergänzt dies den Rhythmus des Gedichtes durch visuelle Caesuras unterschiedlicher Länge oder schafft Nebeneinanderstellungen, um Bedeutung, Mehrdeutigkeit oder Ironie zu betonen oder einfach eine ästhetisch ansprechende Form zu schaffen. In seiner extremsten Form kann dies zu konkreter Poesie oder asemischer Schrift führen. [87][88]

Diction [ edit ]

Poetic Diction behandelt die Art und Weise, in der Sprache verwendet wird, und bezieht sich nicht nur auf die Sprache to the sound but also to the underlying meaning and its interaction with sound and form.[89] Many languages and poetic forms have very specific poetic dictions, to the point where distinct grammars and dialects are used specifically for poetry.[90][91]Registers in poetry can range from strict employment of ordinary speech patterns, as favoured in much late-20th-century prosody,[92] through to highly ornate uses of language, as in medieval and Renaissance poetry.[93][19659004]Poetic diction can include rhetorical devices such as simile and metaphor, as well as tones of voice, such as irony. Aristotle wrote in the Poetics that "the greatest thing by far is to be a master of metaphor."[94] Since the rise of Modernism, some poets have opted for a poetic diction that de-emphasizes rhetorical devices, attempting instead the direct presentation of things and experiences and the exploration of tone.[95] On the other hand, Surrealists have pushed rhetorical devices to their limits, making frequent use of catachresis.[96]

Allegorical stories are central to the poetic diction of many cultures, and were prominent in the West during classical times, the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Aesop's Fablesrepeatedly rendered in both verse and prose since first being recorded about 500 BCE, are perhaps the richest single source of allegorical poetry through the ages.[97] Other notables examples include the Roman de la Rosea 13th-century French poem, William Langland's Piers Ploughman in the 14th century, and Jean de la Fontaine's Fables (influenced by Aesop's) in the 17th century. Rather than being fully allegorical, however, a poem may contain symbols or allusions that deepen the meaning or effect of its words without constructing a full allegory.[98]

Another element of poetic diction can be the use of vivid imagery for effect. The juxtaposition of unexpected or impossible images is, for example, a particularly strong element in surrealist poetry and haiku.[99] Vivid images are often endowed with symbolism or metaphor. Many poetic dictions use repetitive phrases for effect, either a short phrase (such as Homer's "rosy-fingered dawn" or "the wine-dark sea") or a longer refrain. Such repetition can add a somber tone to a poem, or can be laced with irony as the context of the words changes.[100]

Specific poetic forms have been developed by many cultures. In more developed, closed or "received" poetic forms, the rhyming scheme, meter and other elements of a poem are based on sets of rules, ranging from the relatively loose rules that govern the construction of an elegy to the highly formalized structure of the ghazal or villanelle.[101] Described below are some common forms of poetry widely used across a number of languages. Additional forms of poetry may be found in the discussions of the poetry of particular cultures or periods and in the glossary.

Sonnet[edit]

Among the most common forms of poetry, popular from the Late Middle Ages on, is the sonnet, which by the 13th century had become standardized as fourteen lines following a set rhyme scheme and logical structure. By the 14th century and the Italian Renaissance, the form had further crystallized under the pen of Petrarch, whose sonnets were translated in the 16th century by Sir Thomas Wyatt, who is credited with introducing the sonnet form into English literature.[102] A traditional Italian or Petrarchan sonnet follows the rhyme scheme ABBA, ABBA, CDECDEthough some variation, perhaps the most common being CDCDCD, especially within the final six lines (or sestet), is common.[103] The English (or Shakespearean) sonnet follows the rhyme scheme ABAB, CDCD, EFEF, GGintroducing a third quatrain (grouping of four lines), a final couplet, and a greater amount of variety with regard to rhyme than is usually found in its Italian predecessors. By convention, sonnets in English typically use iambic pentameter, while in the Romance languages, the hendecasyllable and Alexandrine are the most widely used meters.

Sonnets of all types often make use of a voltaor "turn," a point in the poem at which an idea is turned on its head, a question is answered (or introduced), or the subject matter is further complicated. This volta can often take the form of a "but" statement contradicting or complicating the content of the earlier lines. In the Petrarchan sonnet, the turn tends to fall around the division between the first two quatrains and the sestet, while English sonnets usually place it at or near the beginning of the closing couplet.

Sonnets are particularly associated with high poetic diction, vivid imagery, and romantic love, largely due to the influence of Petrarch as well as of early English practitioners such as Edmund Spenser (who gave his name to the Spenserian sonnet), Michael Drayton, and Shakespeare, whose sonnets are among the most famous in English poetry, with twenty being included in the Oxford Book of English Verse.[104] However, the twists and turns associated with the volta allow for a logical flexibility applicable to many subjects.[105] Poets from the earliest centuries of the sonnet to the present have utilized the form to address topics related to politics (John Milton, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Claude McKay), theology (John Donne, Gerard Manley Hopkins), war (Wilfred Owen, e.e. cummings), and gender and sexuality (Carol Ann Duffy). Further, postmodern authors such as Ted Berrigan and John Berryman have challenged the traditional definitions of the sonnet form, rendering entire sequences of "sonnets" that often lack rhyme, a clear logical progression, or even a consistent count of fourteen lines.

Shi[edit]

Shi (simplified Chinese: 诗; traditional Chinese: 詩; pinyin: shī; Wade–Giles: shih) Is the main type of Classical Chinese poetry.[106] Within this form of poetry the most important variations are "folk song" styled verse (yuefu), "old style" verse (gushi), "modern style" verse (jintishi). In all cases, rhyming is obligatory. The Yuefu is a folk ballad or a poem written in the folk ballad style, and the number of lines and the length of the lines could be irregular. For the other variations of shi poetry, generally either a four line (quatrain, or jueju) or else an eight-line poem is normal; either way with the even numbered lines rhyming. The line length is scanned by an according number of characters (according to the convention that one character equals one syllable), and are predominantly either five or seven characters long, with a caesura before the final three syllables. The lines are generally end-stopped, considered as a series of couplets, and exhibit verbal parallelism as a key poetic device.[107] The "old style" verse (Gushi) is less formally strict than the jintishior regulated verse, which, despite the name "new style" verse actually had its theoretical basis laid as far back as Shen Yue (441–513 CE), although not considered to have reached its full development until the time of Chen Zi'ang (661–702 CE).[108] A good example of a poet known for his Gushi poems is Li Bai (701–762 CE). Among its other rules, the jintishi rules regulate the tonal variations within a poem, including the use of set patterns of the four tones of Middle Chinese. The basic form of jintishi (sushi) has eight lines in four couplets, with parallelism between the lines in the second and third couplets. The couplets with parallel lines contain contrasting content but an identical grammatical relationship between words. Jintishi often have a rich poetic diction, full of allusion, and can have a wide range of subject, including history and politics.[109][110] One of the masters of the form was Du Fu (712–770 CE), who wrote during the Tang Dynasty (8th century).[111]

Villanelle[edit]

The villanelle is a nineteen-line poem made up of five triplets with a closing quatrain; the poem is characterized by having two refrains, initially used in the first and third lines of the first stanza, and then alternately used at the close of each subsequent stanza until the final quatrain, which is concluded by the two refrains. The remaining lines of the poem have an a-b alternating rhyme.[112] The villanelle has been used regularly in the English language since the late 19th century by such poets as Dylan Thomas,[113]W.H. Auden,[114] and Elizabeth Bishop.[115]

Limerick[edit]

A limerick is a poem that consists of five lines and is often humorous. Rhythm is very important in limericks for the first, second and fifth lines must have seven to ten syllables. However, the third and fourth lines only need five to seven. All of the lines must rhyme and have the same rhythm.

Tanka[edit]

Tanka is a form of unrhymed Japanese poetry, with five sections totalling 31 onji (phonological units identical to morae), structured in a 5-7-5-7-7 pattern.[116] There is generally a shift in tone and subject matter between the upper 5-7-5 phrase and the lower 7-7 phrase. Tanka were written as early as the Asuka period by such poets as Kakinomoto no Hitomaro (fl. late 7th century), at a time when Japan was emerging from a period where much of its poetry followed Chinese form.[117] Tanka was originally the shorter form of Japanese formal poetry (which was generally referred to as "waka"), and was used more heavily to explore personal rather than public themes. By the tenth century, tanka had become the dominant form of Japanese poetry, to the point where the originally general term waka ("Japanese poetry") came to be used exclusively for tanka. Tanka are still widely written today.[118]

Haiku[edit]

Haiku is a popular form of unrhymed Japanese poetry, which evolved in the 17th century from the hokkuor opening verse of a renku.[119] Generally written in a single vertical line, the haiku contains three sections totalling 17 onjistructured in a 5-7-5 pattern. Traditionally, haiku contain a kireji, or cutting word, usually placed at the end of one of the poem's three sections, and a kigo, or season-word.[120] The most famous exponent of the haiku was Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694). An example of his writing:[121]

- 富士の風や扇にのせて江戸土産

- fuji no kaze ya oogi ni nosete Edo miyage

- the wind of Mt. Fuji

- I've brought on my fan!

- a gift from Edo

Khlong[edit]

The khlong (โคลง [kʰlōːŋ]) is among the oldest Thai poetic forms. This is reflected in its requirements on the tone markings of certain syllables, which must be marked with mai ek (ไม้เอก [máj èːk]◌่) or mai tho (ไม้โท [máj tʰōː]◌้). This was likely derived from when the Thai language had three tones (as opposed to today's five, a split which occurred during the Ayutthaya Kingdom period), two of which corresponded directly to the aforementioned marks. It is usually regarded as an advanced and sophisticated poetic form.[122]

In khlonga stanza (botบท [bòt]) has a number of lines (batบาท [bàːt]from Pali and Sanskrit pāda), depending on the type. The bat are subdivided into two wak (วรรค [wák]from Sanskrit varga).[note 1] The first wak has five syllables, the second has a variable number, also depending on the type, and may be optional. The type of khlong is named by the number of bat in a stanza; it may also be divided into two main types: khlong suphap (โคลงสุภาพ [kʰlōːŋ sù.pʰâːp]) and khlong dan (โคลงดั้น [kʰlōːŋ dân]). The two differ in the number of syllables in the second wak of the final bat and inter-stanza rhyming rules.[122]

Khlong si suphap[edit]

The khlong si suphap (โคลงสี่สุภาพ [kʰlōːŋ sìː sù.pʰâːp]) is the most common form still currently employed. It has four bat per stanza (si translates as four). The first wak of each bat has five syllables. The second wak has two or four syllables in the first and third battwo syllables in the second, and four syllables in the fourth. Mai ek is required for seven syllables and Mai tho is required for four, as shown below. "Dead word" syllables are allowed in place of syllables which require mai ekand changing the spelling of words to satisfy the criteria is usually acceptable.

Ode[edit]

Odes were first developed by poets writing in ancient Greek, such as Pindar, and Latin, such as Horace. Forms of odes appear in many of the cultures that were influenced by the Greeks and Latins.[123] The ode generally has three parts: a strophe, an antistrophe, and an epode. The antistrophes of the ode possess similar metrical structures and, depending on the tradition, similar rhyme structures. In contrast, the epode is written with a different scheme and structure. Odes have a formal poetic diction and generally deal with a serious subject. The strophe and antistrophe look at the subject from different, often conflicting, perspectives, with the epode moving to a higher level to either view or resolve the underlying issues. Odes are often intended to be recited or sung by two choruses (or individuals), with the first reciting the strophe, the second the antistrophe, and both together the epode.[124] Over time, differing forms for odes have developed with considerable variations in form and structure, but generally showing the original influence of the Pindaric or Horatian ode. One non-Western form which resembles the ode is the qasida in Persian poetry.[125]

Ghazal[edit]

The ghazal (also ghazel, gazel, gazal, or gozol) is a form of poetry common in Arabic, Persian, Urdu and Bengali poetry. In classic form, the ghazal has from five to fifteen rhyming couplets that share a refrain at the end of the second line. This refrain may be of one or several syllables and is preceded by a rhyme. Each line has an identical meter. The ghazal often reflects on a theme of unattainable love or divinity.[126]

As with other forms with a long history in many languages, many variations have been developed, including forms with a quasi-musical poetic diction in Urdu.[127] Ghazals have a classical affinity with Sufism, and a number of major Sufi religious works are written in ghazal form. The relatively steady meter and the use of the refrain produce an incantatory effect, which complements Sufi mystical themes well.[128] Among the masters of the form is Rumi, a 13th-century Persian poet.[129]

One of the most famous poet in this type of poetry is Hafez, whose poems often include the theme of exposing hypocrisy. His life and poems have been the subject of much analysis, commentary and interpretation, influencing post-fourteenth century Persian writing more than any other author.[130][131] The West-östlicher Diwan of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, a collection of lyrical poems, is inspired by the Persian poet Hafez.[132][133][134]

In addition to specific forms of poems, poetry is often thought of in terms of different genres and subgenres. A poetic genre is generally a tradition or classification of poetry based on the subject matter, style, or other broader literary characteristics.[135] Some commentators view genres as natural forms of literature. Others view the study of genres as the study of how different works relate and refer to other works.[136]

Narrative poetry[edit]

Narrative poetry is a genre of poetry that tells a story. Broadly it subsumes epic poetry, but the term "narrative poetry" is often reserved for smaller works, generally with more appeal to human interest. Narrative poetry may be the oldest type of poetry. Many scholars of Homer have concluded that his Iliad and Odyssey were composed of compilations of shorter narrative poems that related individual episodes. Much narrative poetry—such as Scottish and English ballads, and Baltic and Slavic heroic poems—is performance poetry with roots in a preliterate oral tradition. It has been speculated that some features that distinguish poetry from prose, such as meter, alliteration and kennings, once served as memory aids for bards who recited traditional tales.[137]

Notable narrative poets have included Ovid, Dante, Juan Ruiz, William Langland, Chaucer, Fernando de Rojas, Luís de Camões, Shakespeare, Alexander Pope, Robert Burns, Adam Mickiewicz, Alexander Pushkin, Edgar Allan Poe, Alfred Tennyson, and Anne Carson.

Lyric poetry[edit]

Lyric poetry is a genre that, unlike epic and dramatic poetry, does not attempt to tell a story but instead is of a more personal nature. Poems in this genre tend to be shorter, melodic, and contemplative. Rather than depicting characters and actions, it portrays the poet's own feelings, states of mind, and perceptions.[138] Notable poets in this genre include Christine de Pizan, John Donne, Charles Baudelaire, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Antonio Machado, and Edna St. Vincent Millay.

Epic poetry[edit]

Epic poetry is a genre of poetry, and a major form of narrative literature. This genre is often defined as lengthy poems concerning events of a heroic or important nature to the culture of the time. It recounts, in a continuous narrative, the life and works of a heroic or mythological person or group of persons.[139] Examples of epic poems are Homer's Iliad and OdysseyVirgil's Aeneid, the NibelungenliedLuís de Camões' Os Lusíadasthe Cantar de Mio Cidthe Epic of Gilgameshthe MahabharataValmiki's RamayanaFerdowsi's ShahnamaNizami (or Nezami)'s Khamse (Five Books), and the Epic of King Gesar. While the composition of epic poetry, and of long poems generally, became less common in the west after the early 20th century, some notable epics have continued to be written. Derek Walcott won a Nobel prize to a great extent on the basis of his epic, Omeros.[140]

Satirical poetry[edit]

Poetry can be a powerful vehicle for satire. The Romans had a strong tradition of satirical poetry, often written for political purposes. A notable example is the Roman poet Juvenal's satires.[141]

The same is true of the English satirical tradition. John Dryden (a Tory), the first Poet Laureate, produced in 1682 Mac Flecknoesubtitled "A Satire on the True Blue Protestant Poet, T.S." (a reference to Thomas Shadwell).[142] Another master of 17th-century English satirical poetry was John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester.[143] Satirical poets outside England include Poland's Ignacy Krasicki, Azerbaijan's Sabir and Portugal's Manuel Maria Barbosa du Bocage.

Elegy[edit]

An elegy is a mournful, melancholy or plaintive poem, especially a lament for the dead or a funeral song. The term "elegy," which originally denoted a type of poetic meter (elegiac meter), commonly describes a poem of mourning. An elegy may also reflect something that seems to the author to be strange or mysterious. The elegy, as a reflection on a death, on a sorrow more generally, or on something mysterious, may be classified as a form of lyric poetry.[144][145]

Notable practitioners of elegiac poetry have included Propertius, Jorge Manrique, Jan Kochanowski, Chidiock Tichborne, Edmund Spenser, Ben Jonson, John Milton, Thomas Gray, Charlotte Turner Smith, William Cullen Bryant, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Evgeny Baratynsky, Alfred Tennyson, Walt Whitman, Antonio Machado, Juan Ramón Jiménez, Giannina Braschi, William Butler Yeats, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Virginia Woolf.

Verse fable[edit]

The fable is an ancient literary genre, often (though not invariably) set in verse. It is a succinct story that features anthropomorphized animals, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature that illustrate a moral lesson (a "moral"). Verse fables have used a variety of meter and rhyme patterns.[146]

Notable verse fabulists have included Aesop, Vishnu Sarma, Phaedrus, Marie de France, Robert Henryson, Biernat of Lublin, Jean de La Fontaine, Ignacy Krasicki, Félix María de Samaniego, Tomás de Iriarte, Ivan Krylov and Ambrose Bierce.

Dramatic poetry[edit]

Dramatic poetry is drama written in verse to be spoken or sung, and appears in varying, sometimes related forms in many cultures. Greek tragedy in verse dates to the 6th century B.C., and may have been an influence on the development of Sanskrit drama,[147] just as Indian drama in turn appears to have influenced the development of the bianwen verse dramas in China, forerunners of Chinese Opera.[148]East Asian verse dramas also include Japanese Noh. Examples of dramatic poetry in Persian literature include Nizami's two famous dramatic works, Layla and Majnun and Khosrow and ShirinFerdowsi's tragedies such as Rostam and SohrabRumi's MasnaviGorgani's tragedy of Vis and Raminand Vahshi's tragedy of Farhad.

Speculative poetry[edit]

Speculative poetry, also known as fantastic poetry (of which weird or macabre poetry is a major sub-classification), is a poetic genre which deals thematically with subjects which are "beyond reality", whether via extrapolation as in science fiction or via weird and horrific themes as in horror fiction. Such poetry appears regularly in modern science fiction and horror fiction magazines. Edgar Allan Poe is sometimes seen as the "father of speculative poetry".[149] Poe's most remarkable achievement in the genre was his anticipation, by three-quarters of a century, of the Big Bang theory of the universe's origin, in his then much-derided 1848 essay (which, due to its very speculative nature, he termed a "prose poem"), Eureka: A Prose Poem.[150][151]

Prose poetry[edit]

Prose poetry is a hybrid genre that shows attributes of both prose and poetry. It may be indistinguishable from the micro-story (a.k.a. the "short short story", "flash fiction"). While some examples of earlier prose strike modern readers as poetic, prose poetry is commonly regarded as having originated in 19th-century France, where its practitioners included Aloysius Bertrand, Charles Baudelaire, Arthur Rimbaud and Stéphane Mallarmé.[152] Since the late 1980s especially, prose poetry has gained increasing popularity, with entire journals, such as The Prose Poem: An International Journal,[153]Contemporary Haibun Online,[154] and Haibun Today[155] devoted to that genre and its hybrids. Latin American poets of the 20th century who wrote prose poems include Octavio Paz and Giannina Braschi[156][157]

Light poetry[edit]

Light poetry, or light verse, is poetry that attempts to be humorous. Poems considered "light" are usually brief, and can be on a frivolous or serious subject, and often feature word play, including puns, adventurous rhyme and heavy alliteration. Although a few free verse poets have excelled at light verse outside the formal verse tradition, light verse in English usually obeys at least some formal conventions. Common forms include the limerick, the clerihew, and the double dactyl.

While light poetry is sometimes condemned as doggerel, or thought of as poetry composed casually, humor often makes a serious point in a subtle or subversive way. Many of the most renowned "serious" poets have also excelled at light verse. Notable writers of light poetry include Lewis Carroll, Ogden Nash, X. J. Kennedy, Willard R. Espy, and Wendy Cope.

Slam poetry[edit]

Slam poetry is a genre, developed since about 1984, in which performers comment emotively, aloud before an audience, on personal, social, or other matters. It focuses on the aesthetics of word play, intonation, and voice inflection. Slam poetry is often competitive, at dedicated "poetry slam" contests.[158]

See also[edit]

- ^ In literary studies, line in western poetry is translated as bat. However, in some forms, the unit is more equivalent to wak. To avoid confusion, this article will refer to wak and bat instead of linewhich may refer to either.

References[edit]

- ^ "Poetry". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. 2013.

- ^ "Poetry". Merriam-Webster. Merriam-Webster, Inc. 2013.

- ^ "Poetry". Dictionary.com. Dictionary.com, LLC. 2013—Based on the Random House Dictionary

- ^ Oral Literature in Africa, Ruth Finnegan, Open Book Publishers, 2012

- ^ Strachan, John R; Terry, Richard, G (2000). Poetry: an introduction. Edinburgh University Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-8147-9797-6.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Eliot, TS (1999). "The Function of Criticism". Selected Essays. Faber & Faber. pp. 13–34. ISBN 978-0-15-180387-3.

- ^ Longenbach, James (1997). Modern Poetry After Modernism. Oxford University Press. pp. 9, 103. ISBN 0-19-510178-2.

- ^ Schmidt, Michael, ed. (1999). The Harvill Book of Twentieth-Century Poetry in English. Harvill Press. pp. xxvii–xxxiii. ISBN 1-86046-735-0.

- ^ Hoivik, S; Luger, K (3 June 2009). "Folk Media for Biodiversity Conservation: A Pilot Project from the Himalaya-Hindu Kush". International Communication Gazette. 71 (4): 321–346. doi:10.1177/1748048509102184.

- ^ a b Goody, Jack (1987). The Interface Between the Written and the Oral. Cambridge University Press. p. 98. ISBN 0-521-33794-1.

- ^ Sanders, NK (trans.) (1972). The Epic of Gilgamesh (Revised ed.). Pinguin-Bücher. pp. 7–8.

- ^ Mark, Joshua J. (13 August 2014). "The World's Oldest Love Poem".

- ^ ARSU, SEBNEM. "Oldest Line In The World". New York Times. New York Times. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- ^ Ahl, Frederick; Roisman, Hannah M (1996). The Odyssey Re-Formed. Cornell University Press. pp. 1–26. ISBN 0-8014-8335-2..

- ^ Ebrey, Patricia (1993). Chinese Civilisation: A Sourcebook (2nd ed.). The Free Press. pp. 11–13. ISBN 978-0-02-908752-7.

- ^ Abondolo, Daniel (2001). A poetics handbook: verbal art in the European tradition. Curzon. S. 52–53. ISBN 978-0-7007-1223-6.

- ^ Gentz, Joachim (2008). "Ritual Meaning of Textual Form: Evidence from Early Commentaries of the Historiographic and Ritual Traditions". In Kern, Martin. Text and Ritual in Early China. University of Washington Press. pp. 124–48. ISBN 978-0-295-98787-3.

- ^ Habib, Rafey (2005). A history of literary criticism. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 607–09, 620. ISBN 978-0-631-23200-1.

- ^ Heath, Malcolm, ed. (1997). Aristotle's Poetics. Pinguin-Bücher. ISBN 0-14-044636-2.

- ^ Frow, John (2007). Genre (Reprint ed.). Routledge. pp. 57–59. ISBN 978-0-415-28063-1.

- ^ Bogges, WF (1968). "'Hermannus Alemannus' Latin Anthology of Arabic Poetry". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 88 (4): 657–70. doi:10.2307/598112. JSTOR 598112.Burnett, Charles (2001). "Learned Knowledge of Arabic Poetry, Rhymed Prose, and Didactic Verse from Petrus Alfonsi to Petrarch". Poetry and Philosophy in the Middle Ages: A Festschrift for Peter Dronke. Brill Academic Publishers. pp. 29–62. ISBN 90-04-11964-7.

- ^ Grendler, Paul F (2004). The Universities of the Italian Renaissance. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 239. ISBN 0-8018-8055-6.

- ^ Kant, Immanuel; Bernard, JH (trans.) (1914). Critique of Judgment. Macmillan. p. 131.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link) Kant argues that the nature of poetry as a self-consciously abstract and beautiful form raises it to the highest level among the verbal arts, with tone or music following it, and only after that the more logical and narrative prose.

- ^ Ou, Li (2009). Keats and negative capability. Continuum. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-1-4411-4724-0.

- ^ Watten, Barrett (2003). The constructivist moment: from material text to cultural poetics. Wesleyan University Press. pp. 17–19. ISBN 978-0-8195-6610-2.

- ^ Abu-Mahfouz, Ahmad (2008). "Translation as a Blending of Cultures" (PDF). Journal of Translation. 4 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2012.

- ^ Highet, Gilbert (1985). The classical tradition: Greek and Roman influences on western literature (Reissued ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 355, 360, 479. ISBN 978-0-19-500206-5.

- ^ Wimsatt, William K, Jr; Brooks, Cleanth (1957). Literary Criticism: A Short History. Vintage Bücher. p. 374.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Johnson, Jeannine (2007). Why write poetry?: modern poets defending their art. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-8386-4105-7.

- ^ Jenkins, Lee M; Davis, Alex, eds. (2007). The Cambridge companion to modernist poetry. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–7, 38, 156. ISBN 978-0-521-61815-1.CS1 maint: Uses editors parameter (link)

- ^ Barthes, Roland (1978). "Death of the Author". Image-Music-Text. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. pp. 142–48.

- ^ Connor, Steven (1997). Postmodernist culture: an introduction to theories of the contemporary (2nd ed.). Blackwell. pp. 123–28. ISBN 978-0-631-20052-9.

- ^ Bloom, Harold (2006). Bloom's Modern Critical Views: Contemporary Poets. Bloom's Literary Criticism, Infobase Publishing, p.7.

- ^ Pinsky 1998, p. 52

- ^ Fussell 1965, pp. 20–21

- ^ Schülter, Julia (2005). Rhythmic Grammar. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 24, 304, 332.

- ^ Yip, Moira (2002). Tone. Cambridge textbooks in linguistics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–4, 130. ISBN 0-521-77314-8.

- ^ Fussell 1965, p. 12

- ^ Jorgens, Elise Bickford (1982). The well-tun'd word : musical interpretations of English poetry, 1597–1651. Universität von Minnesota Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8166-1029-7.

- ^ Fussell 1965, pp. 75–76

- ^ Walker-Jones, Arthur (2003). Hebrew for biblical interpretation. Society of Biblical Literature. pp. 211–13. ISBN 978-1-58983-086-8.

- ^ Bala Sundara Raman, L; Ishwar, S; Kumar Ravindranath, Sanjeeth (2003). "Context Free Grammar for Natural Language Constructs: An implementation for Venpa Class of Tamil Poetry". Tamil Internet: 128–36.

- ^ Hartman, Charles O (1980). Free Verse An Essay on Prosody. Northwestern University Press. pp. 24, 44, 47. ISBN 978-0-8101-1316-9.

- ^ Hollander 1981, p. 22

- ^ McClure, Laura K. (2002), Sexuality and Gender in the Classical World: Readings and SourcesOxford, England: Blackwell Publishers, p. 38, ISBN 978-0-631-22589-8

- ^ Corn 1997, p. 24

- ^ Corn 1997, pp. 25, 34

- ^ a b Annis, William S (January 2006). "Introduction to Greek Meter" (PDF). Aoidoi. pp. 1–15.

- ^ "Examples of English metrical systems" (PDF). Fondazione Universitaria in provincia di Belluno. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ Fussell 1965, pp. 23–24

- ^ "Portrait Bust". britishmuseum.org. The British Museum.

- ^ Kiparsky, Paul (September 1975). "Stress, Syntax, and Meter". Language. 51 (3): 576–616. doi:10.2307/412889. JSTOR 412889.

- ^ Thompson, John (1961). The Founding of English Meter. Columbia University Press. p. 36.

- ^ Pinsky 1998, pp. 11–24

- ^ Pinsky 1998, p. 66

- ^ Nabokov, Vladimir (1964). Notes on Prosody. Bollingen Foundation. pp. 9–13. ISBN 978-0-691-01760-0.

- ^ Fussell 1965, pp. 36–71

- ^ Nabokov, Vladimir (1964). Notes on Prosody. Bollingen Foundation. S. 46–47. ISBN 0-691-01760-3.

- ^ Adams 1997, p. 206

- ^ Adams 1997, p. 63

- ^ "What is Tetrameter?". tetrameter.com. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ Adams 1997, p. 60

- ^ James, ED; Jondorf, G (1994). Racine: Phèdre. Cambridge University Press. S. 32–34. ISBN 978-0-521-39721-6.

- ^ Corn 1997, p. 65

- ^ Osberg, Richard H (2001). "'I kan nat geeste': Chaucer's Artful Alliteration". In Gaylord, Alan T. Essays on the art of Chaucer's Verse. Routledge. pp. 195–228. ISBN 978-0-8153-2951-0.

- ^ Alighieri, Dante; Pinsky Robert (trans.) (1994). "Einführung". The Inferno of Dante: A New Verse Translation. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. ISBN 0-374-17674-4.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ a b Kiparsky, Paul (Summer 1973). "The Role of Linguistics in a Theory of Poetry". Daedalus. 102 (3): 231–44.

- ^ Russom, Geoffrey (1998). Beowulf and old Germanic metre. Cambridge University Press. pp. 64–86. ISBN 978-0-521-59340-3.

- ^ Liu, James JY (1990). Art of Chinese Poetry. University Of Chicago Press. S. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-226-48687-1.

- ^ Wesling, Donald (1980). The chances of rhyme. University of California Press. pp. x–xi, 38–42. ISBN 978-0-520-03861-5.

- ^ Menocal, Maria Rosa (2003). The Arabic Role in Medieval Literary History. University of Pennsylvania. p. 88. ISBN 0-8122-1324-6.

- ^ Sperl, Stefan, ed. (1996). Qasida poetry in Islamic Asia and Africa. Glattbutt. p. 49. ISBN 978-90-04-10387-0.

- ^ Adams 1997, pp. 71–104

- ^ Fussell 1965, p. 27

- ^ Adams 1997, pp. 88–91

- ^ Corn 1997, pp. 81–82, 85

- ^ Whitworth, Michael H (2010). Reading modernist poetry. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-4051-6731-4.

- ^ Hollander 1981, pp. 50–51

- ^ Corn 1997, pp. 7–13

- ^ Corn 1997, pp. 78–82

- ^ Corn 1997, p. 78

- ^ Dalrymple, Roger, ed. (2004). Middle English Literature: a guide to criticism. Blackwell Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-631-23290-2.

- ^ Corn 1997, pp. 78–79

- ^ McTurk, Rory, ed. (2004). Companion to Old Norse-Icelandic Literature and Culture. Blackwell. pp. 269–80. ISBN 978-1-4051-3738-6.

- ^ Freedman, David Noel (July 1972). "Acrostics and Metrics in Hebrew Poetry". Harvard Theological Review. 65 (3): 367–92. doi:10.1017/s0017816000001620.

- ^ Kampf, Robert (2010). Reading the Visual – 17th century poetry and visual culture. GRIN Verlag. S. 4–6. ISBN 978-3-640-60011-3.

- ^ Bohn, Willard (1993). The aesthetics of visual poetry. Universität von Chicago Press. S. 1–8. ISBN 978-0-226-06325-6.

- ^ Sterling, Bruce (13 July 2009). "Web Semantics: Asemic writing". Wired. Archived from the original on 2009-10-27. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ Barfield, Owen (1987). Poetic diction: a study in meaning (2nd ed.). Wesleyan University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-8195-6026-1.

- ^ Sheets, George A (Spring 1981). "The Dialect Gloss, Hellenistic Poetics and Livius Andronicus". American Journal of Philology. 102 (1): 58–78. doi:10.2307/294154. JSTOR 294154.

- ^ Blank, Paula (1996). Broken English: dialects and the politics of language in Renaissance writings. Routledge. pp. 29–31. ISBN 978-0-415-13779-9.

- ^ Perloff, Marjorie (2002). 21st-century modernism: the new poetics. Blackwell Publishers. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-631-21970-5.

- ^ Paden, William D, ed. (2000). Medieval lyric: genres in historical context. Universität von Illinois Press. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-252-02536-5.

- ^

- ^ Davis, Alex; Jenkins, Lee M, eds. (2007). The Cambridge companion to modernist poetry. Cambridge University Press. pp. 90–96. ISBN 978-0-521-61815-1.CS1 maint: Uses editors parameter (link)

- ^ San Juan, E, Jr (2004). Working through the contradictions from cultural theory to critical practice. Bucknell University Press. pp. 124–25. ISBN 978-0-8387-5570-9.

- ^ Treip, Mindele Anne (1994). Allegorical poetics and the epic: the Renaissance tradition to Paradise Lost. University Press of Kentucky. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-8131-1831-4.

- ^ Crisp, P (1 November 2005). "Allegory and symbol – a fundamental opposition?". Language and Literature. 14 (4): 323–38. doi:10.1177/0963947005051287.

- ^ Gilbert, Richard (2004). "The Disjunctive Dragonfly". Modern Haiku. 35 (2): 21–44.

- ^ Hollander 1981, pp. 37–46

- ^ Fussell 1965, pp. 160–65

- ^ Corn 1997, p. 94

- ^ Minta, Stephen (1980). Petrarch and Petrarchism. Manchester University Press. pp. 15–17. ISBN 0-7190-0748-8.

- ^ Quiller-Couch, Arthur, ed. (1900). Oxford Book of English Verse. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Fussell 1965, pp. 119–33

- ^ Watson, Burton (1971). CHINESE LYRICISM: Shih Poetry from the Second to the Twelfth Century. (New York: Columbia University Press). ISBN 0-231-03464-4, 1

- ^ Watson, Burton (1971). Chinese Lyricism: Shih Poetry from the Second to the Twelfth Century. (New York: Columbia University Press). ISBN 0-231-03464-4, 1–2 and 15–18

- ^ Watson, Burton (1971). Chinese Lyricism: Shih Poetry from the Second to the Twelfth Century. (New York: Columbia University Press). ISBN 0-231-03464-4, 111 and 115

- ^ Faurot, Jeannette L (1998). Drinking with the moon. China Books & Periodicals. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-8351-2639-7.

- ^ Wang, Yugen (1 June 2004). "Shige: The Popular Poetics of Regulated Verse". T'ang Studies. 2004 (22): 81–125. doi:10.1179/073750304788913221.

- ^ Schirokauer, Conrad (1989). A brief history of Chinese and Japanese civilizations (2nd ed.). Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-15-505569-8.

- ^ Kumin, Maxine (2002). "Gymnastics: The Villanelle". In Varnes, Kathrine. An Exaltation of Forms: Contemporary Poets Celebrate the Diversity of Their Art. University of Michigan Press. p. 314. ISBN 978-0-472-06725-1.

- ^ "Do Not Go Gentle into that Good Night" in Thomas, Dylan (1952). In Country Sleep and Other Poems. New Directions Publications. p. 18.

- ^ "Villanelle", in Auden, WH (1945). Collected Poems. Random House.

- ^ "One Art", in Bishop, Elizabeth (1976). Geography III. Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

- ^ Samy Alim, H; Ibrahim, Awad; Pennycook, Alastair, eds. (2009). Global linguistic flows. Taylor und Francis. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-8058-6283-6.CS1 maint: Uses editors parameter (link)

- ^ Brower, Robert H; Miner, Earl (1988). Japanese court poetry. Stanford University Press. pp. 86–92. ISBN 978-0-8047-1524-9.

- ^ McCllintock, Michael; Ness, Pamela Miller; Kacian, Jim, eds. (2003). The tanka anthology: tanka in English from around the world. Red Moon Press. pp. xxx–xlviii. ISBN 978-1-893959-40-8.

- ^ Corn 1997, p. 117

- ^ Ross, Bruce, ed. (1993). Haiku moment: an anthology of contemporary North American haiku. Charles E. Tuttle Co. p. xiii. ISBN 978-0-8048-1820-9.

- ^ Etsuko Yanagibori. "Basho's Haiku on the theme of Mt. Fuji". The personal notebook of Etsuko Yanagibori. Archived from the original on 28 May 2007.

- ^ a b "โคลง Khloong". Thai Language Audio Resource Center. Thammasat University. Retrieved 6 March 2012. Reproduced form Hudak, Thomas John (1990). The indigenization of Pali meters in Thai poetry. Monographs in International Studies, Southeast Asia Series. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Center for International Studies. ISBN 978-0-89680-159-2.

- ^ Gray, Thomas (2000). English lyrics from Dryden to Burns. Elibron. pp. 155–56. ISBN 978-1-4021-0064-2.

- ^ Gayley, Charles Mills; Young, Clement C (2005). English Poetry (Reprint ed.). Kessinger Publishing. p. lxxxv. ISBN 978-1-4179-0086-2.

- ^ Kuiper, edited by Kathleen (2011). Poetry and drama literary terms and concepts. Britannica Educational Pub. in association with Rosen Educational Services. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-61530-539-1.CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ Campo, Juan E (2009). Encyclopedia of Islam. Infobase p. 260. ISBN 978-0-8160-5454-1.

- ^ Qureshi, Regula Burckhardt (Autumn 1990). "Musical Gesture and Extra-Musical Meaning: Words and Music in the Urdu Ghazal". Journal of the American Musicological Society. 43 (3): 457–97. doi:10.1525/jams.1990.43.3.03a00040.

- ^ Sequeira, Isaac (1 June 1981). "The Mystique of the Mushaira". The Journal of Popular Culture. 15 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1981.4745121.x.

- ^ Schimmel, Annemarie (Spring 1988). "Mystical Poetry in Islam: The Case of Maulana Jalaladdin Rumi". Religion & Literature. 20 (1): 67–80.

- ^ Yarshater. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ^ Hafiz and the Place of Iranian Culture in the World by Aga Khan III, November 9, 1936 London.

- ^ Shamel, Shafiq (2013). Goethe and Hafiz. ISBN 978-3-0343-0881-6. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ "Goethe and Hafiz". Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ "GOETHE". Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ Chandler, Daniel. "Introduction to Genre Theory". Aberystwyth University. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ Schafer, Jorgen; Gendolla, Peter, eds. (2010). Beyond the screen: transformations of literary structures, interfaces and genres. Verlag. pp. 16, 391–402. ISBN 978-3-8376-1258-5.CS1 maint: Uses editors parameter (link)

- ^ Kirk, GS (2010). Homer and the Oral Tradition (reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 22–45. ISBN 978-0-521-13671-6.

- ^ Blasing, Mutlu Konuk (2006). Lyric poetry : the pain and the pleasure of words. Princeton University Press. pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-0-691-12682-1.

- ^ Hainsworth, JB (1989). Traditions of heroic and epic poetry. Modern Humanities Research Association. pp. 171–75. ISBN 978-0-947623-19-7.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1992: Derek Walcott". Swedish Academy. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ Dominik, William J; Wehrle, T (1999). Roman verse satire: Lucilius to Juvenal. Bolchazy-Carducci. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-0-86516-442-0.

- ^ Black, Joseph, ed. (2011). Broadview Anthology of British Literature. 1. Broadview Press. p. 1056. ISBN 978-1-55481-048-2.

- ^ Treglown, Jeremy (1973). "Satirical Inversion of Some English Sources in Rochester's Poetry". Review of English Studies. 24 (93): 42–48. doi:10.1093/res/xxiv.93.42.

- ^ Pigman, GW (1985). Grief and English Renaissance elegy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 40–47. ISBN 978-0-521-26871-4.

- ^ Kennedy, David (2007). Elegy. Routledge. pp. 10–34. ISBN 978-1-134-20906-4.

- ^ Harpham, Geoffrey Galt; Abrams, MH. A glossary of literary terms (10th ed.). Wadsworth Cengage Learning. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-495-89802-3.

- ^ Keith, Arthur Berriedale Keith (1992). Sanskrit Drama in its origin, development, theory and practice. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-81-208-0977-2.

- ^ Dolby, William (1983). "Early Chinese Plays and Theatre". In Mackerras, Colin. Chinese Theater: From Its Origins to the Present Day. Universität von Hawaii Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-8248-1220-1.

- ^ Allen, Mike (2005). Dutcher, Roger, ed. The alchemy of stars. Science Fiction Poetry Association. pp. 11–17. ISBN 978-0-8095-1162-4.

- ^ Rombeck, Terry (January 22, 2005). "Poe's little-known science book reprinted". Lawrence Journal-World & News.

- ^ Robinson, Marilynne, "On Edgar Allan Poe", The New York Review of Booksvol. LXII, no. 2 (5 February 2015), pp. 4, 6.

- ^ Monte, Steven (2000). Invisible fences: prose poetry as a genre in French and American literature. Universität von Nebraska Press. pp. 4–9. ISBN 978-0-8032-3211-2.

- ^ "The Prose Poem: An International Journal". Providence College. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ "Contemporary Haibun Online". Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ "Haibun Today".

- ^ "Poetry Foundation: Octavio Paz".

- ^ "Modern Language Association Presents Giannina Braschi". Circumference Magazine: Poetry in Translation, Academy of American Poets. January 1, 2013. Considered one of the most revolutionary Latin American poets writing today, Giannina Braschi, author of the epic prose poem 'Empire of Dreams'.

- ^ [1]

Bibliography[edit]

Further reading[edit]

This audio file was created from a revision of the article "Poetry" dated 2005-04-20, and does not reflect subsequent edits to the article. (Audio help)

Wikiquote has quotations related to: Poetry

Wikisource has original works on the topic: Poetry

Look up poetry in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Poetry.

- Brooks, Cleanth (1947). The Well Wrought Urn: Studies in the Structure of Poetry. Harcourt Brace & Company.

- Finch, Annie (2011). A Poet's Ear: A Handbook of Meter and Form. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-05066-6.

- Fry, Stephen (2007). The Ode Less Travelled: Unlocking the Poet Within. Pfeil Bücher. ISBN 978-0-09-950934-9.

- Pound, Ezra (1951). ABC of Reading. Faber.

- Preminger, Alex; Brogan, Terry VF; Warnke, Frank J (eds.). The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (3rd ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02123-6.CS1 maint: Uses editors parameter (link)

- Tatarkiewicz, Władysław, "The Concept of Poetry", translated by Christopher Kasparek, Dialectics and Humanism: The Polish Philosophical Quarterlyvol. II, no. 2 (Spring 1975), published in Warsaw under the auspices of the Polish Academy of Sciences by Polish Scientific Publishers, pp. 13–24. (The text contains some typographical errors.) A revised Polish-language version of this article appears as "Dwa pojęcia poezji" ("Two Concepts of Poetry") in the author's ParergaWarsaw, Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1978, pp. 20–38. Tatarkiewicz identifies two distinct concepts subsumed within the term "poetry": traditional poetic form (rhymed, rhythmic verse), now no longer deemed obligatory; and poetic content—a certain state of mind—which can be evoked not only by verbal arts but also by other arts—painting, sculpture, especially music—as well as by nature, scenery, history, and everyday life.

Anthologies[edit]

- Isobel Armstrong, Joseph Bristow, and Cath Sharrock (1996) Nineteenth-Century Women Poets. An Oxford Anthology

- Ferguson, Margaret; Salter, Mary Jo; Stallworthy, Jon, eds. (1996). The Norton Anthology of Poetry (4th ed.). W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-96820-0.CS1 maint: Uses editors parameter (link)

- Gardner, Helen, ed. (1972). New Oxford Book of English Verse 1250–1950. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-812136-9.

- Larkin, Philip, ed. (1973). The Oxford Book of Twentieth Century English Verse. Oxford University Press.

- Lonsdale, Roger, ed. (1990). Eighteenth Century Women Poets by Roger Lonsdale. Oxford University Press.

- Mosley, Ivo, ed. (1994). The Green Book of Poetry. Frontier Publishing. ISBN 978-1-872914-06-0.

- Mosley, Ivo, ed. (1996). Earth Poems: Poems from Around the World to Honor The Earth. Harpercollins ISBN 978-0-06-251283-3.

- Ricks, Christopher, ed. (1999). The Oxford Book of English Verse. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-214182-1.

- Yeats, WB, ed. (1936). Oxford Book of Modern Verse 1892–1935. Oxford University Press.

Es gibt eine breite Palette von Namen für andere Fußtypen, bis hin zu einem Choriamb, einem viersilbigen metrischen Fuß mit einer betonten Silbe, gefolgt von zwei unbelasteten Silben und dem Schließen mit einer gestressten Silbe. Der Choriamb stammt aus einigen alten griechischen und lateinischen Gedichten. [48] Sprachen, die Vokallänge oder Intonation anstelle von oder zusätzlich zu silabischen Akzenten, wie osmanisches Türkisch oder Vedisch, verwenden, haben oft ähnliche Konzepte wie Iamb und Dactyl um gewöhnliche Kombinationen von langen und kurzen Klängen zu beschreiben. [52]

Jeder dieser Fußtypen hat ein gewisses "Gefühl", entweder allein oder in Kombination mit anderen Füßen. Das Iamb zum Beispiel ist die natürlichste Form des Rhythmus in der englischen Sprache und erzeugt im Allgemeinen einen subtilen, aber stabilen Vers. [53] Der Scanning-Meter kann oft das grundlegende oder grundlegende Muster eines Verses zeigen, zeigt jedoch nicht das Variieren Stress, sowie die unterschiedlichen Tonhöhen und Längen der Silben. [54]